Reggatta de Blanc: A Deep Dive Retrospective of The Police

Click below on the streaming service of your choice to listen to the playlist as your read along.

The Police came together as a band in 1977 and called it quits in 1986. While there was a reunion and tour in 2007, they have not released any new music since their final album in 1983. During that first decade they issued five albums, in which four went to #1 in the UK while the other was a top ten. In the US, they scored a #1, two top tens, and two top forties. In the UK, they had five #1 singles while the rest, save one, reached the top forty. In the US they had a #1 single and six more top tens. It was about as tidy and perfect a career as a band could desire.

The Police gathered critical appreciation and a broad swath of fans across the musical spectrum – from punk to jazz to pop to reggae – a rare feat for a hugely popular act. Fellow musicians also frequently sing their praises as top performers at their respective crafts.

The Playlist

“Fall Out”

“Dead End Job”

“Next to You”

“Hole In My Life”

“Truth Hits Everybody”

“Masoko Tanga”

“Deathwish”

“The Bed’s Too Big Without You”

“Does Everyone Stare”

“No Time This Time”

“Driven to Tears”

“When the World Is Running Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around”

“Canary in A Coalmine”

“Voices Inside My Head”

“Hungry for You”

“Too Much Information”

“One World (Not Three)”

“Omegaman”

“Darkness”

“Low Life”

“Murder By Numbers”

“Walking in Your Footsteps”

“Tea In the Sahara”

“Someone to Talk To”

This phenomenal success seemed improbable when this trio assembled out of prog rock, jazz, and classical backgrounds. It seemed less likely when they proceeded to create music by blending punk, 1960s rock ‘n’ roll, and reggae. Their songs also had variety and could be dark, fun, complex, or straightforward, further layering the contradictions and absurdities that countered a likely recipe for popularity. And yet, in terms of success, they outdid almost all of their contemporaries of the late ‘70s first generation of modern rock artists.

One final paradox to complete this picture of The Police before we get into their music. While still celebrated and appreciated today, The Police don’t always get their due. Forbes has a list of The 30 Best Rock Bands of all Time and omits the band. On Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the 100 Greatest Artists of all Time, the trio clocks in only at #70; and they are at #120 (out of 125) in Billboard magazine’s list of greatest artists. IMDB has a list of the top 100 rock bands, in which Sting ranks #92 but The Police didn’t make the cut. How can a band be commercially successful, loved by a diverse audience of fans, be critically lauded, yet get little consideration among the ranks of top rock bands?

We will try to answer this question by giving The Police the Ceremony ‘deep dive’ treatment. We’ll skip the hits and explore a playlist of deeper cuts to explore their discography and learn what their musical career was all about. Personally, I’ve tended to enjoy their album tracks as much or more than their hits, so if you’re only a casual fan, this will hopefully be rewarding.

“Fall Out” \ non-album single (1977)

“Dead End Job” \ B-side to “Can’t Stand Losing You” (UK) and “Roxanne” (North America) (1978)

A foundational component to The Police was the intriguing Copeland family. Miles Copeland Jr was an arranger and trumpet player for the Glenn Miller Orchestra but made his career as a CIA officer. He was in counterintelligence (i.e. a spy) in the US army during WWII and then played a role in the creation of the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner to the CIA for which he was also a founding member. Lorraine Adie was a Scottish archaeologist and also a secret agent with the Special Operations Executive during WWII, which is when she met Miles. They married, lived all over the world in pursuit of their careers, and had four children, two of whom are central to the story of The Police.

Stewart Copeland was the drummer in the progressive rock band, Curved Air, and had met Gordon ‘Sting’ Sumner while touring the UK in 1976. Sumner was a school teacher who also played bass in jazz bands around his hometown of Newcastle upon Tyne. He had gotten his nickname from a bandmate due to the black and yellow striped, wasp-like sweater he often wore on stage. The timing was fortuitous when Sting reached out to Copeland in early ’77 after having moved to London. Curved Air had recently called it quits, so the duo agreed to work together.

One of the founding tenets of punk was that it was a rejection of progressive rock and its complex musicianship and lengthy compositions. So, it was surprising that Copeland was keen to make the turn from his prog pedigree into the emerging punk sound. Sting was hesitant yet open to the experiment. They joined with French guitarist Henry Padovani, who had also just arrived in London looking to join a punk band. They called themselves The Police as a provocation amongst the discordant relations between authorities and the punk community in 1977 England.

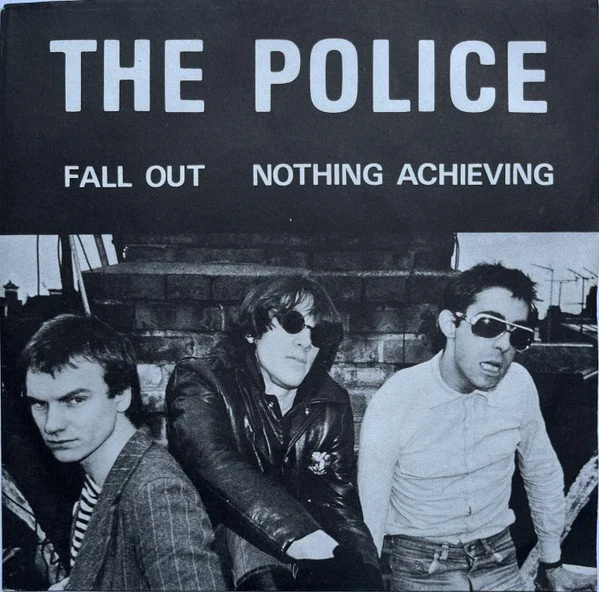

The cover for the single, “Fall Out,” with Sting, Copeland, and Padovani

They recorded the song, “Fall Out,” before starting to play gigs around London in the spring of ’77. It was released on May 1 by Illegal Records, a label formed by Stewart and his brother, Miles. Given Copeland and Sting’s playing experience in more proficient musical forms, this was not the typical DIY punk act of the time; though Padovani’s guitar skills were still a bit rough and Stewart helped on rhythm guitar for the recording. “Fall Out” was a tight, power pop track, quickly delivered with frenetic drumming and a lively bassline. Perhaps more punk adjacent than pure to the form, it was a capable single but failed to make a mark.

Concurrent to the release of their first single, Sting was being courted by another band that was coming together, Strontium 90. The band was also looking for a drummer, so Sting brought Copeland along. Strontium 90’s guitarist was Andy Summers, who had been playing and touring with various bands since the late ‘60s, including Soft Machine and The Animals. Strontium 90 did some demos and played a couple shows, but didn’t turn into anything. What it did achieve was getting Andy to join The Police.

Summers chafed at sharing guitar duties with the less skilled Padovani as the quartet made its way through the summer of ’77. He gave the band an ultimatum to make him the sole guitarist or he’d depart. Padovani was out and The Police returned to being a trio. Henry would soon join the band Wayne County and the Electric Chairs, who at the time were better known than The Police. He would later form the band The Myster Five’s out of dissolution of the Electric Chairs, and then had his own act, The Flying Padovanis. Needless to say, while having some level of success, his trajectory would not track in the way of The Police’s.

After writing songs and continuing to play gigs, The Police strengthened and broadened their sound, building on the punk base with accents of reggae, power pop, and jazz. For three white men in London, the decision to incorporate reggae was particularly curious. Summers explained it in 1979 in an interview in Big Noise magazine:

“Well, we live in London. There's a big West Indie community there. Reggae's very popular there. Bob Marley's quite popular, you know. And so, we've all been listening to it for awhile. Then it started creeping into our rehearsals. We just started jamming reggae without even discussing it. And when Sting wrote “Roxanne,” it was the first song we ever really treated as having a reggae feel. And even then, we really didn't think it was reggae. What we did was take the elements from reggae, the basic elements, and used to them to our own end. Because I felt what we do is not really reggae, it's a blending of rock and reggae. We're one of the first groups ever doing that, really.”

More recently, in a YouTube interview with Rick Beato, Summers talked about how he liked the guitar sound on the reggae rhythms and how they filled the studio. For a trio that all came from varied backgrounds both culturally and musically, there were no barriers to how they wanted to shape their music, and it’s no surprise it went into a unique space.

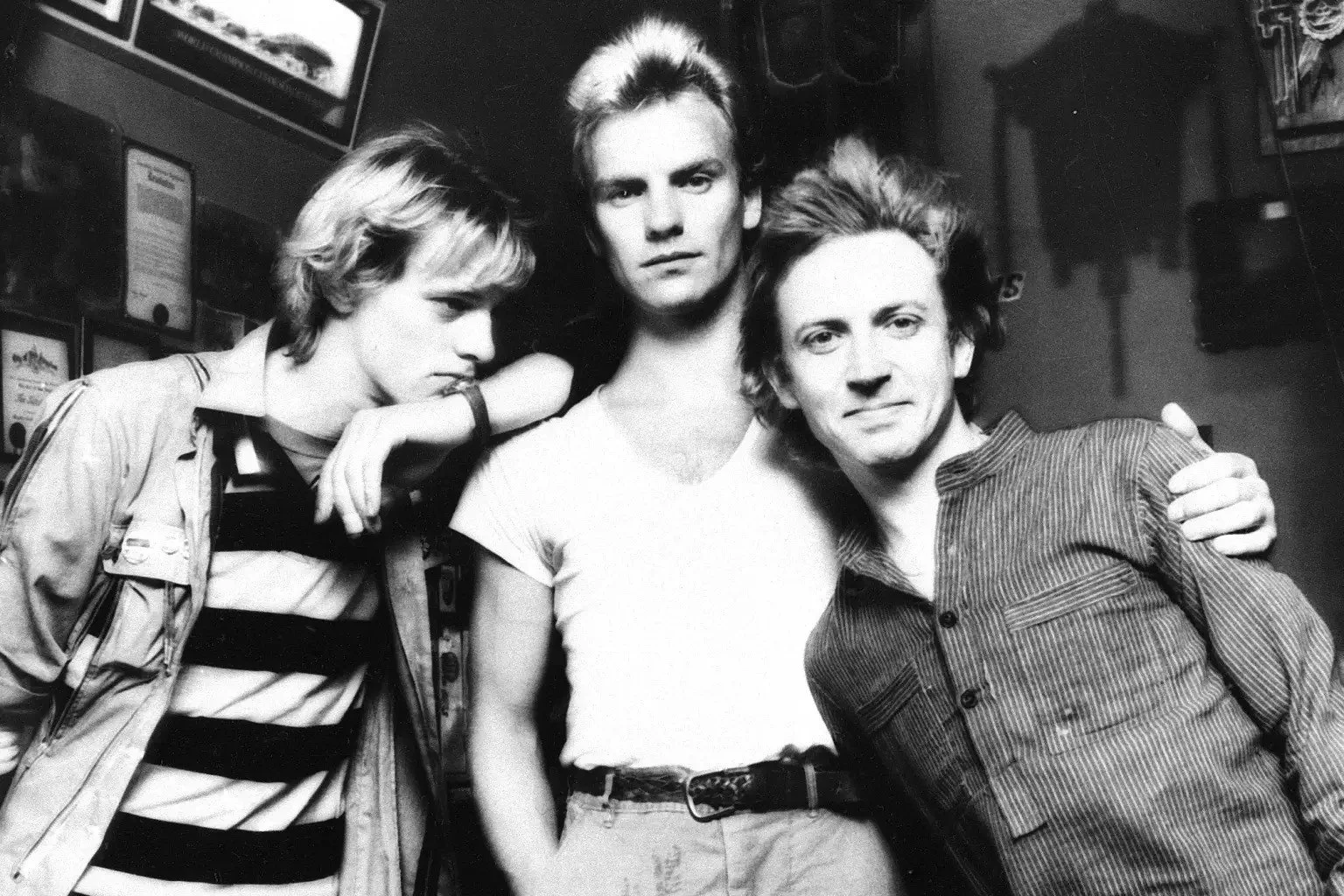

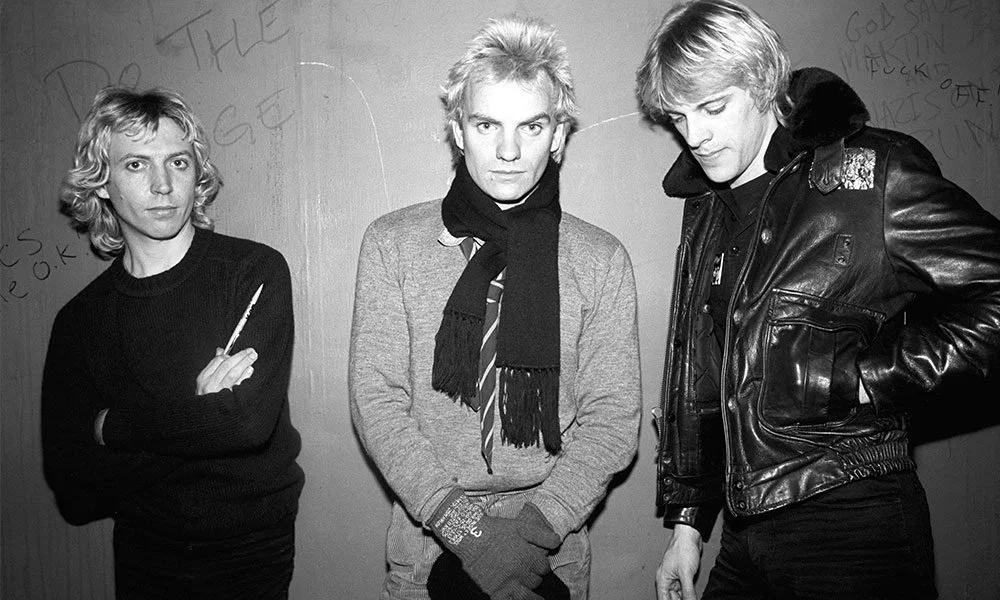

The Police in 1979, L to R, Stewart Copeland, Sting, and Andy Summers

Without a recording deal, they began recording their songs on a shoestring budget. One of those songs was, “Roxanne,” which was a strong enough calling card for Miles Copeland to shop the band to labels, landing them a contract with A&M Records. The single was released in April 1978 but failed to gain attention.

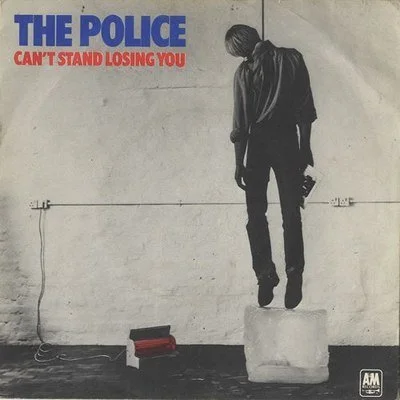

Their second single, “Can’t Stand Losing You,” was issued in August. It reached #42 in the UK singles chart. It’s B-side was, “Dead End Job,” a strident, punky single in which Sting effectively declared the end of his teaching career. With “Roxanne” being about a prostitute and the cover for the single of “Can’t Stand Losing You” being a picture of Copeland hanging himself, The Police were certainly adhering to their punk ethos and challenging the conventional boundaries of acceptance.

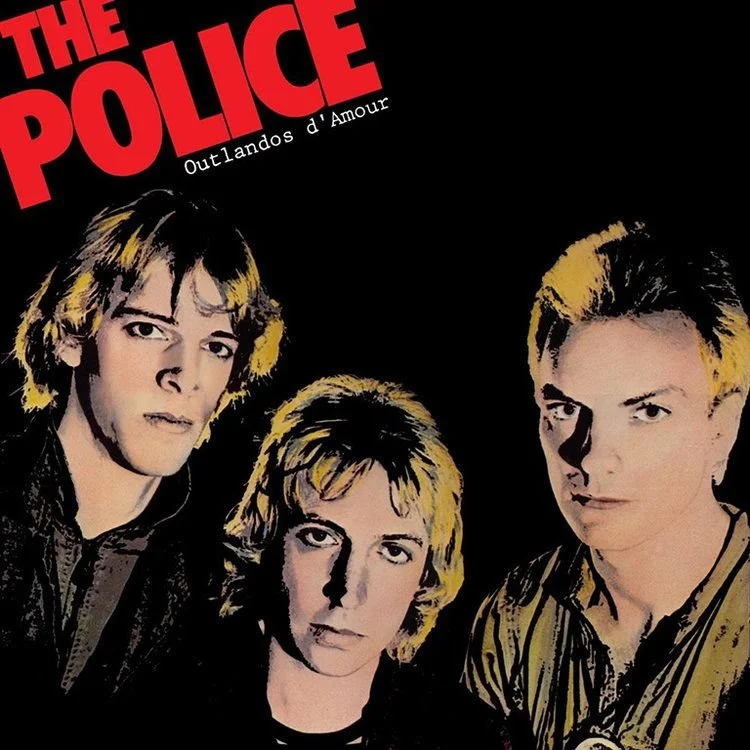

“Next to You”; “Hole in My Life”; “Truth Hits Everybody”; “Masoko Tanga” \ Outlandos D’Amour (1978)

The first album was released in November 1978 and included the prior singles except for “Fall Out.” “So Lonely” was the next single and it failed to chart. In February, “Roxanne” was issued as a single in North America and it became a minor hit, reaching the top forty in both the US and Canada. This led to its re-release in the UK, a performance on Top of the Pops (in true punk fashion, Sting makes no attempt to pretend it’s not a lip-synched performance, as was standard on the show), and a peak position of #12 in the UK singles chart. Likewise, “Can’t Stand Losing You” was also re-issued and reached #2 in the UK. The Police were suddenly an international success, driving the album to the UK top ten and a top forty spot in the US.

Outlandos d’Amour (which translates to ‘Outlaws of Love’), was an interesting collection of songs for the time. While punk was the band’s founding impetus, The Police’s sound harkened more to punk’s descendents, 1960s rock ‘n’ roll and 1970s pub rock. The opening track, “Next to You,” was a straightforward pub rocker, quick, simple, and catchy. “Born in the 50’s” and “Truth Hits Everybody” delivered in the same vein. However, “So Lonely,” “Roxanne,” and “Can’t Stand Losing You” displayed the band’s distinct use of reggae rhythms mixed with power pop.

“Hole in My Life” and “Masoko Tanga” were the tracks that revealed the special something The Police were going to bring to rock and pop music. It wouldn’t be long before it was established that Summers was a great guitarist, Sting a clever bassist, and Copeland an inventive drummer. But they didn’t just play well, they could bring those talents to bear on intriguing and creative compositions. The repeated and off-kilter rhythms of “Hole in My Life” and ultra-catchy, dub reggae sound of “Masoko Tanga” were unlike anything else in 1978. Ska was yet to have its second wave, though Elvis Costello was playing with some reggae influences in tracks like, “Watching the Detectives” (1977), but there weren’t other notable examples of reggae being incorporated into rock in this way.

The band did their first North American tour in the fall of 1978. Still mostly unknown, they were playing in bars and small clubs. This has created a ‘were you there’ lore around the shows, whether it was CBGBs in New York or The Horseshoe Tavern in Toronto.

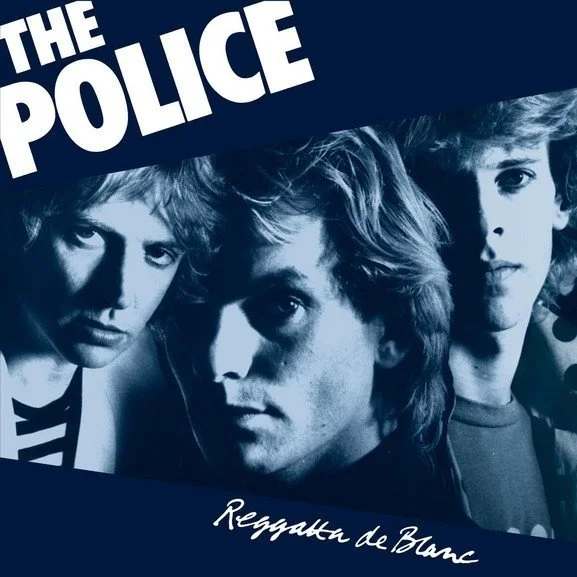

“Deathwish”; “The Bed’s Too Big Without You”; “Does Everyone Stare”; “No Time This Time” \ Reggatta de Blanc (1979)

Released in October ’79, eleven months after their debut, the second album again featured a French title, this time tipping to their unique sound; Reggatta de Blanc translated roughly to ‘white reggae.’ The band went into the studio this time without prepared material and had to draw on earlier tracks written by Copeland prior to joining the band or by Sting from his early ‘70s jazz band, Last Exit. Recorded quickly and cheaply, it nevertheless continued the band’s progression and showcased their talent and ability to write both catchy and complex songs.

The LP’s first single, “Message in A Bottle,” resulted in their first UK #1, repeated by the second single, “Walking on the Moon.” The album also topped the UK album chart and reached the top forty in the US and top ten in Canada. This supported their first world tour as The Police were suddenly a bona fide success.

Musically, the album remained tied to the power pop structures of the first LP, as heard on tunes like, “It’s Alright for You,” the title track (which won a Grammy for best rock instrumental), or “No Time This Time.” Dub reggae drove the wonderfully atmospheric, “Walking on the Moon,” as well as “Deathwish” and the fantastic, jazzy, “The Bed’s Too Big Without You.” A straight reggae rhythm paced the chorus of “Bring on the Night,” and “Does Everyone Stare” rode a jaunty, staccato piano. The opening track was “Message in a Bottle,” their first undeniable smash. It distilled their reggae-rock sound while allowing all the musicians to showcase their talent, packaged in an ultra-catchy, rocking, pop song.

“Driven to Tears”; “When the World Is Running Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around”; “Canary in A Coalmine”; “Voices Inside My Head” \ Zenyatta Mondatta (1980)

The Police kept pace on their third LP, released a year later, almost to the day. Once again, the title was not English but did draw from French language. Zenyatta Mondatta were invented words intended to be playful and that riffed on Zen Buddhism, anti-colonial Kenyan President, Jomo Kenyatta, and the French words for ‘world’ (monde) and ‘reggae’ (once again, regatta).

The LP was again recorded quickly, but this time not due to financial constraints but because of their success, as they were under time pressure to depart for their next world tour. Written while on the prior tour, the band has expressed misgivings about the quality and consistency of the LP. However, it has stood the test of time as remaining in step with their previous work both musically and commercially. The album reached #1 in the UK and #5 in the US. It also reached the top ten in many other countries. The singles, “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” and “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da,” reached #1 and #5 in the UK and also delivered their first top ten US singles.

“Don’t Stand So Close to Me” was about a relationship between a teacher and student, providing a dark element to the song’s brooding, yet catchy composition. It was a great example of how The Police could be accessible, subversive, and complex all in one song. This was how they remained critically lauded, appreciated by fans of both popular and avant-garde music, and topping the charts and dominating the radio dial. Few bands have been able to pull this off so effectively.

The gibberish lyrics of “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da” belied the wonderfully airy chorus that alternated with the stripped down verses. Again, the band mixed pop with their reggae-pop sound brilliantly.

Zenyatta Mondatta also offered the strongest batch of deep cuts in their discography. After the opening track, “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” the next four tracks were “Driven to Tears,” “When the World is Running Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around,” “Canary in A Coalmine,” and “Voices Inside of My Head.” They were an amazing sequence of songs. Not one of them resembled the other, yet all drew on the band’s signature elements of tight pop, edgy rock, dub reggae, and airy riffs. They all caught your ear, each with their own hook whether it was guitar, bass, or drums. There was no single approach the band used to seduce you.

The Police were also known for their bleached blond hair

“Hungry for You”; “Too Much Information”; “One World (Not Three)”; “Omegaman”; “Darkness” \ Ghost in the Machine (1981)

“Low Life” \ B-side to “Spirits in the Material World” (1981)

At age eleven and just starting to define my burgeoning interest in music, I received Ghost in the Machine as part of a trio of albums for Christmas in 1981 (the others were Best of Blondie and Beauty and the Beat by The Go-Go’s). Released that October, again one year following the prior LP, The Police’s fourth LP enthralled me and established my personal appreciation for the band.

The Ghost in the Machine album was the band’s first to be in all English and to not feature their photos. However, the three characters, emblematic of the evolving digital era of the 1980s and the album’s title, were styled to represent the heads of the band members: Summers, Sting, and Copeland.

Achieving their third consecutive #1 in the UK and coming close in the US at #2 (it was held from the top slot by The Rolling Stone’s, Tattoo You, and then Foreigner’s, 4), Ghost in the Machine kept The Police in the top ranks of the music world. It was again paced by an impeccable batch of singles. “Invisible Sun” was only issued in the UK and reached #2. “Every Little Thing She Does is Magic” gave them another UK #1 and “Spirits in the Material World” peaked at #12. That duo also gave them a top ten and top twenty, respectively, in the US. “Secret Journey” was issued as a single in 1982 in North America but didn’t chart in Canada and fell just short of the top forty in the US.

As always, The Police’s core appeal was providing fantastic sounding, unique tracks. The three singles launched the album and each were different, winning you over with different aural appeal. Using keyboards and sax for the first time, the album also offered new sonic dynamics. “Spirits…” was built around a reggae keyboard rhythm, “Every Little Thing…” alternated between brooding verses and a bright, catchy chorus, while “Invisible Sun” pulsated menacingly on a dark foundation of keyboards and drums. Followed by “Hungry for You” and “Demolition Man,” it was an impressive side to the album.

The second side was no less engaging, with the likes of “One World (Not Three),” “Omegaman,” and “Darkness.” And while reggae continued to flavour this album, there was less of it. The only appearance of dub was in the rhythm of “One World.” What the album did introduce were more frenetic, intricate tracks such as “Demolition Man,” “Re-Humanise Yourself,” and “Omegaman.” The band also showed they had a stable of quality songs beyond the LPs, which would surface as B-sides. “Low Life” was on the flip side to “Spirits…” and was a nice example of their moody reggae-pop and new use of sax to change up their sound.

The album was produced by Hugh Padgham, marking a change after Nigel Gray had helmed the first three. It was also recorded in the Caribbean and Canada instead of the UK. After the hurried approach to Zenyatta, the band took more time to compose and record the LP. This allowed them to drive their creativity to new lengths, reinvigorating the band.

A good representation of The Police’s rapid ascent to the upper echelons of the pop and rock worlds was the size of venues on their tours. My home of Canada, and Toronto in particular, embraced the band and they reciprocated. After those first two shows at The Horseshoe Tavern in 1978, they had come through Toronto every year after. In 1979, they played three shows, two in the spring at the cozy venue, The Edge, and then moved up to the ex-movie theatre in the fall, The Music Hall (now known as The Danforth Music Hall). In 1980, buoyed by the successes of Reggatta de Blanc and Zenyatta Mondatta, they swung through mid-sized arenas in Canada and graduated to the venerated, 3000+ seat Massey Hall in Toronto.

The ad for the first Police Picnic in 1981

In 1981, The Police really entrenched their relationship with Toronto when they held the first of their three ‘Police Picnics.’ These were one-day festivals with impressive line-ups. The inaugural event was held on a farm in nearby Oakville and was attended by over 25,000 people. The line-up included Toronto’s own Nash the Slash, Payola$ from Vancouver, The Specials, The Go-Go’s, Killing Joke, and Iggy Pop. In 1982 and 1983, the Picnics were larger in size but had smaller line-ups. Held in Exhibition Stadium in the city, attendance topped 35,000 for each festival. 1982 saw Joan Jett and The Blackhearts, Talking Heads, The English Beat, and A Flock of Seagulls in the line-up. 1983’s Picnic included Simple Minds, James Brown, and Peter Tosh. Moving from a bar to headlining a festival in three years was an impressive ramp-up for the band and indicative of their mass appeal.

For reasons that will soon be clear, Toronto did not see The Police again until 2007, when they did four shows – two in July and another pair in November – in the city’s hockey arena, the Air Canada Centre. Alas, I did not go and, being too young during their first run of shows in my city, have never seen The Police.

“Murder By Numbers” \ B-side to “Every Breath You Take” (1983)

“Walking in Your Footsteps”; “Tea I\in the Sahara” \ Synchronicity (1983)

“Someone to Talk To” \ B-side to “Wrapped Around Your Finger” (1983)

1982 was the first year The Police did not release an album since their debut in ’78, though they toured extensively. Sting and Summers also moved away from England and the entire trio worked on outside projects.

Therefore, after having released an album every fall for four consecutive years, it was a little less than two years later when their fifth LP, Synchronicity, was released in June 1983. What a difference a couple years made. As much as Ghost in the Machine enthralled me, Synchronicity left me underwhelmed. It’s more ambient, down tempo, and pop feel was out of step with my evolving tastes into new wave and post-punk. Perhaps it was the ubiquity of the band that year that was a turn-off, as The Police embraced the new video era and their smash singles dominated the airwaves both on radio and on MuchMusic (Canada’s equivalent channel to MTV). Though I bought Synchronicity and listened to it for awhile, it wasn’t long before I cast it aside. Even today, while I appreciate the artistry of the album and acknowledge it’s a solid collection of songs, I still consider it The Police’s least interesting album.

I was in the minority with this reaction. The album was the band’s fourth straight #1 in the UK and, for the first time, did the same in the US. The lead single, “Every Breath You Take,” went to #1 on both sides of the ocean and either topped the chart or reached the top ten in countries around the world. The next three singles also charted highly, with “Wrapped Around Your Finger” reaching the top ten in the UK and US and “Synchronicity II” and “King of Pain” reaching the top twenty. It was the band’s greatest commercial success.

The album completed the band’s evolution away from their reggae stylings, though still used plenty of space and mood to craft their tunes. Featuring much less punky pop, the band instead employed a more arena friendly expansiveness in the title tracks, “Synchronicity I” and “Synchronicity II.”

The video for “Synchronicity II” saw the band in a post-apocalyptic set of instruments and speakers. This video, along with “Every Breath You Take” and the candle-filled, “Wrapped Around Your Finger,” were all in high rotation on MTV and MuchMusic.

The album’s broad success, however, was driven by the emotional appeal of their ballads. “Walking in Your Footsteps” rode an intricate, clever percussion pattern with echoey guitars. The entire second side was a quartet of sulky tracks. The menacing “Every Breath You Take” became a giant of the era and the band’s signature song. I’ve always found it a curiosity that for a band of such musicianship and creativity, they scored their biggest hit with one of their simplest and most repetitive songs. “King of Pain,” “Wrapped Around Your Finger,” and “Tea in the Sahara” were all slow, spacey tracks – each with their own sublime effects, but with similarly simpler and more direct approaches than seen in prior LPs. It was a sign of where Sting was going musically, as would soon be heard in his solo work.

It should be noted, as a counterpoint to the LP’s stadium anthems and moody ballads, Synchronicity also included one of the least approachable and edgy tracks of their discography, “Mother.” It was sung by Andy Summers, as was “Someone to Talk To,” a non-album track that appeared as the B-side to, “Wrapped Around Your Finger,” and a more digestible example of his intriguing compositions. There were also some lovely, bluesy pop on offer via the album track, “O My God,” and on another non-album B-side, “Murder By Numbers” (included as a bonus track on the cassette and CD versions). Finally, Copeland also got into the mix with his fun track, “Miss Gradenko,” which harkened back to some of the frenetic pop of the prior LP.

Incredibly, despite being at the peak of their commercial success, the band was unable to hold together through to another LP. Sting found tremendous success with his first solo LP, 1984’s The Dream of the Blue Turtles, while Copeland and Summers also worked on separate projects. Sting and Copeland performed Police tracks at the Live Aid concert in 1985 and the band played three shows in ’86 for the Amnesty International ‘A Conspiracy of Hope’ tour. They also went to the studio to work on a new album, but the project was abandoned and the band decided to call it quits. It appeared Sting had more interest in developing his solo work than continuing to work with The Police. Perhaps also, after having climbed to the top of the mountain, there was nothing else for The Police to do.

There was no further word from The Police until they reunited in 2007 for their thirtieth anniversary, going on tour through to 2008 but not issuing any new music. They have re-recorded and re-released various versions of their singles over the years but have maintained there will be no resumption of the band as a creative entity. Sting has enjoyed a sustained career of critical and commercial success, having released fifteen solo albums. His first seven releases all reached the top ten in the UK and US, with …Nothing Like the Sun (1987) and The Soul Cages (1991) reaching #1 in the UK.

Andy Summers has issued solo albums (mostly instrumental) but focused more on film soundtrack work and photography. He recorded two albums with Robert Fripp from King Crimson in the 1980s. Stewart Copeland has excelled in his soundtracks for film and games while also guesting for other artists. He briefly had a band in the late ‘80s, Animal Logic.

From 1978 to 1983, The Police were one of the most consistent and highly successful bands on the planet. Their music was critically adored, and they had fans from genres ranging from punk to pop to reggae to jazz. Case in point, a close friend of mine in the early ‘80s was into heavy metal, yet The Police was one of his favourite bands. Their sound had a consistent sonic foundation of rock, pop, reggae, and jazz, while also evolving in complexity, variation, and instrumentation over their five albums.

However, the writers of music history seem determined to leave them aside. Why? My best guess is that they were, despite all their success, serially underrated. While critically appreciated, their sound was not pure enough to classic rock, new wave, or pop to be considered influential or groundbreaking enough. The mix of reggae into rock and their darkly tinted pop songs were seen as more novel than serious.

Such perspectives aren’t justified. Pull out any album by The Police and let it run and there won’t be a moment that isn’t engaging, provoking, and impressive. And over five albums there was unmistakable progression, exploration, creativity, and all done while constantly throwing out hooks and complex rhythms. Their deep tracks can be as rewarding and engaging than a run through of their greatest hits. This is the sign of a great band, and very few will argue against that opinion when it comes to The Police.