Cover Songs: Volume 5

Click on streaming service of your choice to listen to the playlist as you read along. Note that only the YouTube version has all the songs discussed in this playlist.

This is the fifth installment of an ongoing series exploring the art of the cover song. In the first volume I outlined the various types of cover songs (Straight-up; Modernization; Tempo Change; Genre Change; Reinvention) which provides the framework for my dissection of cover songs. It will help to read the introduction of that first volume before continuing here.

The Playlist

Girls Just Want to Have Fun \ Robert Hazard (1979) & Cyndi Lauper (1983)

Valerie \ The Zutons (2006) & Mark Ronson feat. Amy Winehouse (2007)

Nothing Compares 2 U \ The Family (1985) & Sinéad O’Connor

Spinning Away \ Brian Eno and John Cale (1990) & Sugar Ray (2000)

This Wheel's on Fire \ The Band (1968) & Siouxsie and the Banshees (1987)

Suspended in Gaffa \ Kate Bush (1982) & Ra Ra Riot (2008)

Listen to the Radio: Atmospherics \ Tom Robinson (1983) & Pukka Orchestra (1984)

Physical (You're So) \ Adam and the Ants (1980) & Nine Inch Nails (1992)

This batch of covers doesn’t have too much of a theme, other than perhaps in most cases the cover is much more famous than the original. Certainly, for me, with only one exception in this list, I knew the covers long before I knew the originals. There is also less experimentation and drastic changes between the originals and the covers this time around, with most being straight-up covers. Regardless, these are simply great songs done well by different artists, offering different flavours from a shared recipe.

“Girls Just Want to Have Fun” \ Robert Hazard (1979) & Cyndi Lauper (1983) – Hazard version on YouTube playlist only

“Girls Just Want to Have Fun” was not only one of the biggest hits of the 1980s, it launched the career of a little spitfire from Brooklyn, Cyndi Lauper. The song was perfect for her. It was an anthem for female empowerment and full of energy, allowing Lauper to display her charismatic, flamboyant personality throughout the song and iconic, accompanying video (starring her mother and wrestler Lou Albano). Like several songs from her smash debut LP, She’s So Unusual, it was a cover song (the LP also included a song by Prince, who we’ll visit later in this playlist), though her version would, really, be the only known version and become identified with Lauper as her signature song.

Robert Hazard

Robert Hazard (Robert Rimato) was an American singer and song writer with a journeyman career over the 1970s, dabbling in several styles of music from folk to reggae to rock and punk, never finding way to much success. In 1979 he recorded a demo of “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” that was pure rock ‘n’ roll with a slight punk edge. It was written from the male perspective, suggesting a guy out all night because the girls, they just want to have fun. Why the song wasn’t finished and released is a mystery, because it was catchy, energetic, and had a solid pop sensibility. He wrote the song in twenty minutes while in the shower but considered it, “silly.”

Hazard found some minor success when he shifted to new wave and released an eponymous album in 1982, with the electro-pop song, “Escalator of Life,” charting in early 1983. Otherwise, he never found a musical career more rewarding than having penned Lauper’s smash hit. He passed away in 2008 of pancreatic cancer, just shy of his 60th birthday.

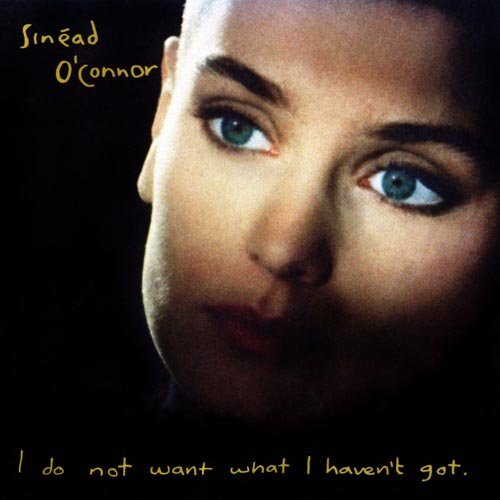

Probably one of my all-time favourite album cover pictures

In 1983, Rick Chertoff was a producer helping Lauper record her first album. She had sung in a rockabilly band, Blue Angel, and had been building a local reputation as a talented prospect in New York. Chertoff heard Hazard’s demo and knew it would be perfect for her. He gained Hazard’s permission to use the song and to change the lyrics, which Lauper requested in order to better position it for a female to sing and to match her direct style. Stripping out the rock edge and building the song around a catchy keyboard riff, the song allowed Lauper’s vocal to come front and centre. The pop vibe was also emphasized with a basic beat and by increasing the girls’ chanting. In all other respects it was very honest to Hazard’s demo, a straight-up cover with a hint of a genre change. Whether the song would have been a hit had anyone other than Cyndi sung it can be debated, but the many covers of it over the years suggest it’s an irrepressible song that succeeds in any format, yet seems fully owned by Lauper even after almost forty years.

“Valerie” \ The Zutons (2006) & Mark Ronson (featuring Amy Winehouse) (2007)

It was just a matter of time writing about cover songs before getting to Mark Ronson, an American DJ, musician, and songwriter who had a very successful album of cover songs in 2007, Version. Until the smash success of 2014’s “Uptown Funk” with Bruno Mars, his most successful single prior was 2007’s, “Valerie,” sung by Amy Winehouse and a cover of a song by The Zutons.

The Zutons

The Zutons were a Liverpool band formed in 2001. They released “Valerie” in 2006 as the second single from their second LP, Tired of Hanging Around. It reached #9 on the UK singles chart, equalling the success of the album’s first single, “Why Won’t You Give Me Your Love.” After enjoying two top twenty singles from their debut LP, The Zutons were making themselves a regular presence in the UK pop scene. However, the band disbanded in 2009 after a line-up change and the release of their third LP, which delivered their third consecutive top ten LP but only one charting single. The Zutons never made much of a dent with North American audiences and remained predominantly a success in the UK and Ireland only.

“Valerie” was in their pop-rock style, continuing the long tradition of punchy, Britpop music. It was written by singer Dave McCabe about his American girlfriend, later revealed as makeup artist, Valerie Star (who indeed had ginger hair), who was living in Florida. Having not paid past fines for speeding tickets, she was arrested under a warrant when caught speeding once again the day before planning to travel to Liverpool to meet McCabe. Unable to travel while negotiating her way out of jail time, it doomed the relationship with McCabe. At least it produced this catchy tune with the lyrics of a man pining for a girl to, “come on over,” and wondering, “Did you have to go to jail? / Put your house on up for sale? / Did you get a good lawyer? / I hope you didn't catch a tan / I hope you find the right man / Who'll fix it for you.” It also explained the video’s prison theme. The song had a casual, swinging feel to it, with sax punctuations from Abi Harding to offset the tight guitar licks from guitarist Boyon Chowdhury, all carried by McCabe’s bluesy, rough-edged vocal. Its American soul vibe would be the element that led to its successful reincarnation a year later.

Mark Ronson, born in England but raised in New York, had issued a first, mildly successful album in 2003 that started his collaborative process with other writers and singers. Each song on the album was sung by a guest artist, mostly from the hip hop world, but also from alternative stars like Jack White of The White Stripes and Rivers Cuomo from Weezer. He was also a regular working producer, starting that work as far back as 1998, but in 2006 he really started to make a mark working with Lily Allen, Christina Aguilera, Robbie Williams, and helming Amy Winehouse’s seminal album, Back to Black. In 2007 he released Version, his second album that continued the guest singer approach but this time featured remixes of popular songs, using sampling and employing a jazzy, retro-Motown style. It was danceable and, with the well-established hooks of the selected hits, had an undeniable catchiness. The album got off to a good start when its first single, a cover of The Smiths’, “Stop Me If You’ve Heard this One Before,” (shortened to just, “Stop Me”), sung by Australian Daniel Merriweather, reached #2 in the UK singles chart. Another top ten was achieved with the Kaiser Chief’s song, “Oh My God,” sung by Lily Allen. There were many good covers on the album, which may just invite inclusions in future cover song volumes. Version peaked at #2 in the UK album chart.

“Valerie” was, of course, sung by the extraordinarily talented but very troubled sensation, Amy Winehouse. Released as the album’s third single, it also reached #2 in the UK chart as well as top ten spots across mainland Europe. The dup were initially challenged in finding a contemporary guitar song that would keep with the album’s theme but was something Winehouse, who was enamoured with her influences of older blues, Motown, and soul music, could get behind. Mark relented to Amy’s suggestion to use The Zutons’ hit from the prior year as a tune that bridged that divide. Her first version was a slower take, but by the time of its debut it had been punched up with a backing beat sampled from The Jam’s, “A Town Called Malice.” Infused with more pop energy than Winehouse’s own music, it offered a different perspective on her impeccable talent. Quicker and lusher, thanks to backing strings, than the original, their cover was true to the original’s feel but carried its own personality, as it only could with Amy on the vocals. It came short of being a reinvention, or even a genre change, and thus was mostly a straight-up cover with a small tempo change.

Ronson and Winehouse’s famous performance at the Brit Awards on Feb 20, 2008

At the time, Winehouse was at the top of her success and fame thanks to the huge, breakout success of her album, Back to Black, released in October 2006. She was making supportive appearances and tours through 2007, helping bolster the album’s growing international success. Version was released in June and “Valerie” was issued as a single in October, bookending the release of Back to Black’s fourth single, “Tears Run Dry on their Own,” which would also become its fourth top twenty hit in the UK. Amy was owning the charts, but a tour in November brought a different result when it was ended short after several poor performances, marred by her severe inebriation. It was, though not realized at the time, the effective end of her short career and the start of a four-year descent towards her death in 2011, propelled by chronic problems with addiction, her relationship with Blake Fielder-Civil, and legal issues related to several assault arrests.

Winehouse would guest on a couple more songs before her death, including a collaboration with Tony Bennett in 2011, but never managed another album over the final, chaotic years of her life. A compilation of her unreleased recordings was issued after her passing, but “Valerie” was her last chart-topping success. Ronson went on to release three more successful albums in 2010, 2015, and 2019, and enjoyed huge hit singles such as “Uptown Funk” and “Nothing Breaks Like A Heart,” which featured Miley Cyrus. Together Amy and Mark carried The Zutons’ song to higher levels of international awareness and success thanks to their talent and the smart, retro-spin they put on a solidly written song.

“Nothing Compares 2 U” \ The Family (1985) & Sinéad O’Connor (1990) – Prince’s version used on Spotify

Prince in 1985

Prince Rogers Nelson was one of those artists that just couldn’t seem to miss. During his ascendency to the highest echelons of the pop world in the 1980s he routinely had his songs also break through for other artists, including, as noted earlier, “When You Were Mine” for Cyndi Lauper. Part of this was due to his constant search for up and coming talent, fostering a stable of artists that he would help by writing, producing, and promoting for his Paisley Park label and creating the ‘Minneapolis sound.’ Artists he fostered included The Time, a band led by Morris Day, Wendy and Lisa, a side project for his Revolution band members, Lisa Coleman and Wendy Melvoin, and percussionist and singer Sheila E (Escovedo). There was also Vanity 6, a vehicle for his girlfriend, Denise Matthews, otherwise known as Vanity. That act became Apollonia 6 when Vanity departed and was replaced by another Prince protégé, Patricia Kotero – aka Apollonia – who took over Vanity’s role in the film, Purple Rain, and her place in the band. “Manic Monday” was originally written and a demo recorded for Apollonia 6 before being abandoned, leaving it free for The Bangles to pick it up in 1986 for their first big hit.

The Family

Prince also liked to use pseudonyms for his side work, and it was in this scenario that he embarked on another side project in 1984, a band called The Family. Formed out of remaining members of The Time after first Morris Day, and then Jesse Johnson, left for solo careers, the remaining members, George ‘Jellybean’ Johnson, Jerome Benton, and ‘St. Paul’ Peterson agreed to work with Prince on the new project. Wendy Melvoin’s sister, Susannah, was brought on to sing and sax player Eric Leeds joined to complete the mix for another venture in the Minneapolis sound.

The band only stayed together for one album, a self-titled release in 1985, which failed to catch on; and neither did its two singles, “The Screams of Passion,” and “High Fashion,” though they did get some chart attention on the US R&B charts. Prince performed most of the music and vocals, mixing vocals from Peterson and Melvoin over his, leaving his own as the backing harmonies. Other than being a minor side note to Prince’s career – he wasn’t credited on the album other than as the writer for the track, “Nothing Compares 2 U” – the project amounted to little when The Family was abandoned with Peterson leaving and the rest of the band being merged into The Revolution.

“Nothing Compares 2 U” was an interesting track and set itself apart on The Family’s album as an emotive ballad compared to the rest of the album’s funk and soul mixes (The Family’s version only appears on the YouTube playlist). Prince wrote the song during a prolific period of writing and recording, as his many projects would reveal, and routinely recorded demos of songs as he captured the onslaught of creativity coming out of his talented mind. His sound engineer at the time, Susan Rogers, has surmised the song originated one day at Flying Cloud Warehouse, his rehearsal space before moving to the famed Paisley Park, when he was agitated over the absence of his young housekeeper, Sandy Scipioni. She was away to be with her family after her father’s passing. As someone who had sold his merchandise at concerts in her youth and helped tend to his needs and give order to his daily life, she was an integral part of Prince’s life. He routinely asked those in the studio with him, “when is Sandy coming back?” So when the lyrics surfaced, “it’s been seven hours and fifteen days / Since you took your love away,” as well as, “All the flowers that you planted mama / In the backyard / All died when you went away,” Rogers’ suspected these were signs of longing for Sandy’s return. As was his style, Prince recorded the song as a sparse demo, working through it to add all the instruments played by him. He then decided to give it to The Family, having Melvoin and Peterson repeat his vocals in order to layer over the Prince’s recording. He then had Leeds add some sax passages and worked with Clare Fischer to add string arrangements, starting a working relationship with the composer-arranger that would last many years.

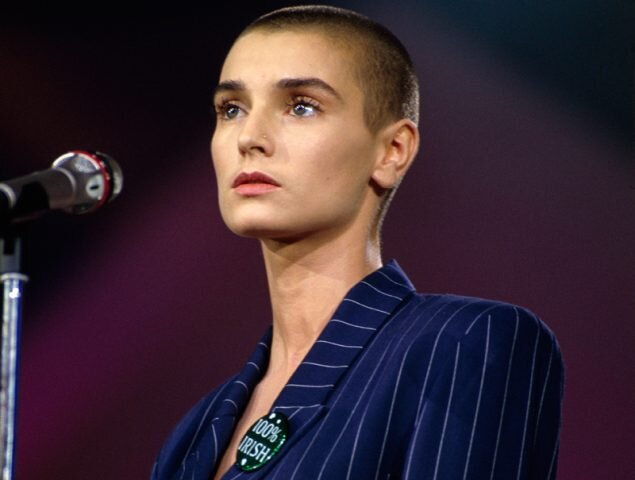

In 1987, one of the most intriguing artists of the past thirty years arrived on the scene. She was an attractive Irish singer with a shaved head that could, in alternate turns, shriek and snarl or whisper and emote with frightening power and dexterity. Sinéad O'Connor was a package of contrasting visuals and sounds that were mesmerizing. Her debut LP, The Lion and the Cobra, launched an improbable career with a top forty placing in both the UK and US, with the single, “Mandinka,” cracking the top twenty in the UK.

Sinéad O’Connor around 1990

Over the course of 1988 and 1989 O’Connor began recording her follow-up LP. Her manager, Fachtna O’Kelly, brought in a cassette of The Family’s album and played “Nothing Compares 2 U.” Chris Hill, co-director of Sinéad’s label, Ensign Records, found it very affecting and encouraged his artist to cover it. When O’Kelly told Sinéad that the song had made Hill cry, she asked, “why, is it that bad?”

Record it she did, keeping the lush strings of the original while recording a powerful vocal over a deep, pulsating beat. The song’s simplicity mixed with her emotive, harmonized vocals, made for an incredible combination. The song was a powerhouse ballad, arresting and stirring, and it catapulted O’Connor’s career. She had removed the synth-funk accents of the original, smoothed it out, and as a result presented the song as a more epic, sweeping, and emotionally stirring track. It was a genre change with a moderate dose of reinvention, though the melody was straight-up, taking its phenomenal hooks and pushing them front and centre, using the combination of the strings and her vocal to bring its stirring elements to a new, powerful height.

Sinéad’s second LP, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, was released in March 1990. It included an earlier single from late 1988, “Jump in the River,” which hadn’t caused much of a stir. “Nothing Compares 2 U” was released as the album’s second single two months prior in January, breaking in the new decade and creating a stir for the LP. Both the song and album reached #1 in the UK, the US, and many other countries. The song’s video, with O’Connor walking through Parc de Saint-Cloud in Paris and of close-ups of her singing against a black backdrop, with tears rolling down her cheek inspired by thoughts of her mother as she sang the song, would be a heavy rotation hit on video channels like MTV. It made her version far better known than The Family’s, a situation that likely holds for many casual fans even now, thirty years later. It would be a peak of commercial success and attention that brought a destabilizing effect to O’Connor’s persona, leading to controversial behaviour that undermined her career. Sinéad has struggled with mental health challenges ever since despite routinely reminding us of her incredible talent over many subsequent releases.

In the spring of 1990, I was in the final semester of my time at college in a semi-rural area of New Jersey. It was a low point for me as I too was struggling with depression. I grabbed onto “Nothing Compares 2 U” and the album as a supportive balm, a soundtrack to my sadness and loneliness that helped me get through the end of the school year and back to my family, friends, and the familiar environment of my hometown Toronto. As a result, this song has long held a greater emotional hold on me and has made me sympathetic to O’Connor’s trials.

As a curious footnote, in 2014 Sinéad shared the story in which she met Prince, summoned to his home in Los Angeles shortly after her version of “Nothing Compares 2 U” had come out. It was the only time they met, and it didn’t go well according to her version of events. They fought and ended up with him chasing her out with a frying pan while she spit at him (sounds like an improbable story but it’s fun picturing it). She felt he didn’t like it that someone outside of his mentorship had made a success of his song. Peterson, of The Family, also corroborated that Prince said he didn’t like O’Connor’s version and didn’t like his songs being covered unless he invited them to do it. I suppose Ensign had obtained appropriate licenses to cover it, paid the required royalties, and avoided having to get explicit consent from Prince himself. Prince also recorded “Nothing Compares 2 U” himself with a guest vocal from Rosie Gaines, including it on his 1993 compilation of hits and B-sides (this is the version on the Spotify playlist). His original 1984 demo, accompanied with footage of him and his band rehearsing at Flying Cloud Warehouse, was also issued by his estate in 2018. Regardless his feelings about O’Connor’s version, the song was a tribute to their individual talents and should be a point of pride for both.

“Spinning Away” \ Brian Eno & John Cale (1990) & Sugar Ray (2000) – Sugar Ray version available on YouTube playlist only

I try to avoid pure, straight-up covers in these playlists since they’re more of a tribute play by the covering artist and usually, unless you just like the novelty of hearing the artist do the song, not worth exploring apart from the original song. I’m making an exception on this one since I love the song and find the combination of artists so intriguing. This is a song that deserves greater attention.

In 1990, the legendary artists Brian Eno and John Cale released an album together, Wrong Way Up. Eno was a pioneer of electronic, experimental, ambient music after his departure from being the keyboardist in the legendary glam band, Roxy Music. He was also a prolific producer, best known for working with David Bowie in the late ‘70s and for shepherding U2 through their most successful albums of the 1980s. Cale was an original member of the ground-breaking, experimental psychedelic 1960s act, the Velvet Underground. He also had done his share of producing and had recorded his own library of varied, experimental music over the ensuing twenty years. Eno had worked with Cale a few times in the past, first playing together in a recording of a live show as part of an ensemble in 1974, then when Eno played on Cale’s album, Fear, the same year, and then again in 1989 on Cale’s song, “The Soul of Carmen Miranda.”

Wrong Way Up was a surprisingly accessible style of pop from the duo. The album was excellent, with more than a few entrancing tunes. I received a promo copy of the CD from my sister-in-law, who worked in the music industry, around 1992 and listened to it quite a bit. Otherwise I wouldn’t have known about the album as it didn’t chart or sell too well, which was a shame given its quality. “Spinning Away” was released as a single on CD in Europe and on vinyl in Germany only, so it didn’t get much attention from English audiences in the UK or North America. It was one of the LP’s most captivating songs. It combined their lovely harmonies with Eno as the lead vocal, was backed by his inventive keyboards and processed beats, and featured lovely guitar accents from Robert Ahwai, a veteran whose work went back to the ‘70s same as Eno and Cale. The song was topped off with sweet strings to bring it to a more ephemeral, dreamy plane that enhanced the song’s core vibe.

Sugar Ray was a band that could not have been more distant from the pedigrees of John Cale and Brian Eno. Formed in the latter half of the ‘80s in Los Angeles, the band toiled in regional obscurity before finally getting signed by Atlantic Records, releasing their debut LP in 1995 as part of the emergent nu metal scene, which merged rap with rock. Success would come in 1997 with their second LP, Floored, and the single, “Fly,” which went to #1 in the US alternative chart. Their next LP, 14:59, and the singles “Every Morning” and “Someday” brought them their first top ten singles in the mainstream chart. Catchy and not without merit, their sound caught some of the zeitgeist of the late ‘90s, which was embraced by many but decried by fans of modern rock as an over-commercialized, over-hyped debasement of quality modern rock.

I admit to having a sympathetic ear for Sugar Ray’s singles but overall was more inclined to just ignore them. Therefore when the Leonardo Dicaprio film, The Beach, came out in 2000 (which, I must admit, I’ve never seen) and its soundtrack included the first new song in seven years from my favourite band, New Order, the exquisite Moby track, “Porcelain” (not yet the hit it would become from his hugely successful LP from the prior year, Play), as well as songs from alternative and electronic acts like Blur, Underworld, Leftfield, Orbital, Barry Adamson, Angelo Badalamenti, and Richard Ashcroft, I was intrigued enough to pick it up.

On the first few listens I wouldn’t pay much attention to the Sugar Ray track, caught in the album’s sixth slot after the intoxicating, mesmerizing electronica of Underworld’s, “8 Ball.” But in time the song increasingly caught my attention, not only because it was a great tune, but it seemed out of character for Sugar Ray, offering a light, laid back feel from the band that, like much of their music, captured the sun-splashed beach feel of their native California (yes, perfect for a movie set on a tropical beach), but avoided the more annoying aspects of their sound. It also had… a nagging familiarity. Finally looking at the credits, I noticed the ‘Eno/Cale’ writing credit and the lightbulb went on. I hadn’t listened to Wrong Way Up in a few years and the Sugar Ray reminder sent me scrambling back to rediscover it all over again, this time appreciating “Spinning Away” to an even greater degree.

This is what a cover can do, even if it’s a straight-up version. Sugar Ray’s version was so close to the original that from the opening notes it was not quite indistinguishable, but it didn’t set itself apart to noticeable degree – even to the point in which the guitar riff was almost exactly reproduced. Indeed, true to their pop form, it was a little more polished, smoothed over, and had more direct vocals, but in losing their usual beats and energy, came out with a subtly affecting track that kept the original’s essence.

So how did Sugar Ray come to cover a lesser-known album track from the likes of Brian Eno and John Cale from ten years prior for a movie? Well, we start with the movie’s director, Danny Boyle, and the album’s supervisor and producer, Pete Tong, both Englishmen well-versed in the country’s renowned acid house scene. The two sought songs and artists that would capture the spirit of the peoplee inhabiting the beach in the movie, using electronic music to convey the otherworldly and free-spirited aspects of the story and its environment. And though not credited on the album, John Cale and Brian Eno consulted with Tong, so that explained how one of their songs came to enter the mix. Giving it to Sugar Ray was an inspired choice, combining the desired style of song with one of the more popular acts of the time, known for sunny, beachy music. It worked and served to bring a very deserving song to greater attention, even if it wasn’t issued as a single. It’s surprising the soundtrack is not available on streaming services, and thus the lack of availability of Sugar Ray’s version on Spotify.

“This Wheel’s on Fire” \ The Band (1968) & Siouxsie & The Banshees (1987)

It is hard to put lists of cover songs together without tripping over Bob Dylan, given how prolifically his songs have been covered, and often done well given the quality of his compositions, over the many decades since his early career. This is a case of his influence, but via another renowned act of his era, The Band.

Bob Dylan and the Band in 1965

The Band was a collection of Canadian (and one American) artists that got their start as The Hawks, playing as the backing band to country, rock, and rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins. In 1964 they started out on their own under a couple of different names, but in 1965 found themselves returned to a backing role, this time for Bob Dylan’s 1965 US tour. Dylan released his fifth and sixth albums that year, Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited respectively, which were the first of his to crack the US top ten (his last three had all reached that level in the UK), and was riding high on his first two top ten singles, “Like A Rolling Stone,” and “Positively 4th Street.” Dylan was also forging new ground for himself by switching from folk to rock, complete with electric guitar, and thus the need for a backing rock band. Therefore, it was understandable that the band, at this point lacking a name and touring under the billing of, ‘Bob Dylan and the Band,’ would choose to ride along with this emerging star.

The group toured with Dylan and recorded with him off and on over 1966 and 1967, contributing to much of his esteemed 1966 double album, Blonde on Blonde. In 1967, Bob was recuperating from a motorcycle injury at a place in Woodstock, New York. His band holed up in a pink house in nearby West Saugerties, which they dubbed ‘Big Pink.’ During this time many demos were recorded with Dylan that would not see the light of day until 1975 as a Dylan release, The Basement Tapes. It was at this point the group adopted the name, The Band, as a nod to their common reference when a backing group. After the Dylan recording sessions, they continued to record at Big Pink, which led to their debut LP in 1968, Music from Big Pink.

The album is one of the most esteemed recordings in the history of Canadian music. It reached the top forty in the US and the single, “The Weight,” didn’t chart as highly but has gone on to be recognized as one of the all-time classics of the era. The album also included three songs written or co-written by Dylan, including his classic, “I Shall Be Released.” “This Wheel’s on Fire” was co-written by Dylan and bassist, Rick Danko, who provided the lead vocal for the track supported with harmonies from Levon Helm. Dylan’s version of the song would later appear on The Basement Tapes, but The Band’s would be the first to see the light of day.

The Band’s version of “This Wheel’s on Fire” was representative of their roots rock sound. It captured the raw sounding guitar of classic rock (from Robbie Robertson) with a cool, breezy vibe complete with string flourishes, Helm’s jazzy syncopation, and some piano and organ accents from Garth Hudson and Richard Manuel. The song’s signature aspects were the verses’ repeated opening lyric, “if your memory serves you well,” which set up the conversational tone of the song. The chorus was a catchy passage, with an accelerating, expansive sound that carried the feverish brinkmanship of the lyric, “This wheel’s on fire / Rolling down the road / Best notify my next of kin / This wheel shall explode.”

For an unassuming, deep album track, “This Wheel’s on Fire” has resonated with many over the years and been covered often. The phrase, ‘wheel’s on fire,’ has been an inviting term given its powerful, illustrative properties. Levon Helm used it as the title of his autobiography. In 1968, Julie Driscoll and Brian Auger and the Trinity did a psychedelic rock version of the song, scoring a UK top ten hit that brought it into broader awareness. Prominent ‘60s act, The Byrds, also released a version on their 1969 LP, Dr. Byrds and Mr Hyde, which in the US ended up being one of their worst performing albums though did reach the top twenty in the UK. Another high profile ’60s band, The Hollies, covered the track as part of their 1969 album of Bob Dylan covers, which reached #3 in the UK chart. Since those early days of the song’s arrival, as many as a dozen other artist have released recorded versions and hundreds have likely played it live. A new version of the song by Julie Driscoll and Adrian Edmondson was used for the theme of the popular British TV series, Absolutely Fabulous, and then pop star Kylie Minogue did a version for the soundtrack of the 2016 film version of the show. In 2006, Canadian singer Serena Ryder issued an album of mostly covers of songs by Canadian artists (this was discussed in the covers volume 3) and included a version of “This Wheel’s on Fire,” but also used the lyric, “if your memory serves you well,” as the album’s title.

Siouxsie and the Banshees, 1987 promo photo for Through the Looking Glass

So, this song has become steeped in history and has repeatedly made its presence known in the music universe. Aside from the Minogue’s cover, most of the versions have remained true to the original and stayed relatively close to the song’s original, roots-rock style. However, perhaps the most surprising and refreshing version of the song arrived in 1987 from dark wave and goth goddess, Siouxsie Sioux, issued on the Siouxsie and the Banshees album, Through the Looking Glass. By then on their seventh LP, the band had been a mainstay in the UK album chart’s top twenty since their debut almost ten years prior. Their sound had been brightening, moving away from the darker tones of their earlier work and revealing a bigger, more rock and pop-oriented take on their sound. Their prior LP, 1986’s Tinderbox, had been their first to crack the US top 100, buoyed by the underground hits, “Cities in Dust,” and “Candyman.”

Later in 1987, Siouxsie cut her hair short, dramatically changing a look she’d carried for the better part of ten years

Through the Looking Glass continued Siouxsie and the Banshees’ progress towards wider popularity and success and led to their minor breakthrough US hit, “Peekaboo,” in 1988. Siouxsie had done excellent covers in the past, most notably with the 1983 version of The Beatles’, “Dear Prudence,” and Through the Looking Glass’ success was propelled by two more. The first was “This Wheel’s on Fire” and the second was the Iggy Pop tune, “The Passenger.” While Iggy was a natural fit for the Banshees, Bob Dylan and The Band were a less obvious choice.

Siouxsie and the Banshees version of “This Wheel’s on Fire” was everything a cover should be. As a child of the ‘80s it was her version I knew long before I learned of its antecedents. The Banshees stayed true to the original, riding the song’s great melody to great effect, but in its sound moved the song to a new genre, modernized it, and in some aspects, reinvented it. The song was bigger, lusher, smoother and more even tempo; it was pop, it was rock, and with her exquisite voice, still had the dark, epic qualities of the goth sound the band had helped forge over their career. It was built on a dramatic bed of strings, driven by a sturdy beat, and accented with scratchy, edgy guitar riffs throughout. The chorus exploded, finally having a vocalist capable of giving the passage the power and grandeur it had so richly deserved. UK audiences agreed, sending the single to a #14 spot, the band’s first top twenty over their past six singles, going back to when “Dear Prudence” hit the top ten four years prior. Once again, The Banshees leveraged a cover song, pulled from a surprising source, to great effect and success.

“Suspended in Gaffa” \ Kate Bush (1982) & Ra Ra Riot (2008)

Covering Kate Bush seems a daunting prospect. Few artists have such a distinct personality and sound such that their music seems so wholly theirs, to the extent that it’s hard to imagine anyone else being able to perform the songs anywhere close to the original – and with Kate Bush, this has proven true. When artists have ventured into her music it’s been for the more pop-styled songs such as “Running Up that Hill” and “Cloudbusting” from her breakthrough album, The Hounds of Love, or her ballads such as, “The Man with the Child in His Eyes” or “This Women’s Work.”

The least likely album to attract covers would be her fourth album, 1982’s The Dreaming. Filled with frenetic and experimental songs that heavily relied on her unique and extraordinary vocal prowess, trying to interpret those songs would be a tall order. Thus, I include Ra Ra Riot’s version of “Suspended in Gaffa” not just because they did a pretty decent job of it, but as much for their moxie in pulling it off.

Ra Ra Riot came out of Syracuse, New York in 2006 as part of that decade’s resurgence of indie rock. After a 2007 EP they released their debut LP in 2008, The Rhumb Line, which included their cover of “Suspended in Gaffa.” In taking on the song, they had to deal with the angular, bouncy piano and the quick dexterity of Bush’s vocal, accented by her own affected, high-pitched backing segments. The chorus alone included several styles of her voice, from deep and hushed, to lushly harmonized, to a spoken element, to that high-pitched, distorted sound. True to the creativity of that period of her career, the song was infused with several sounds from electronics and a variety of instruments not normally found in a pop song, such as a mandolin and a Synclavier (an early, digital synth and sampler).

Ra Ra Riot

Ra Ra Riot’s approach was to widely steer clear of the song’s eccentric elements. Their version maintained the song’s melody and rhythm and thus made it mostly a straight-up cover, and an effective one since the song’s architecture was excellent. Vocalist Wes Miles ably carried the quick lyrics and the use of keyboards, a forceful bass drum and light percussive effects, and a sweet violin presented the song’s core structure. Smartly, Miles didn’t try to emulate any of Bush’s varied vocals (it would have been shocking if he’d been able), instead delivering the song in an understated manner. This resulted in the song shifting from being based on vocal character to more of a whole-band sound, with the vocal working in conjunction with the instruments to offer a more conventional rock song. By doing so, Ra Ra Riot revealed how soundly the song was written, that even stripped of Kate’s vocal pyrotechnics, it was a solid tune with a compelling melody and rhythm that worked in this new form.

Ra Ra Riot’s version of “Suspended in Gaffa” wasn’t released as a single (Bush’s version was in November 1982 as The Dreaming’s fourth single, but didn’t chart), and though The Rhumb Line was a good album it only managed to established the band among indie circles, reaching #14 in the US indie chart. Their subsequent releases would fare better, reaching the mainstream charts.

“Listen to the Radio: Atmospherics” \ Tom Robinson (1983) & Pukka Orchestra (1984)

I love this song, and as a straight-up cover it allows us to listen to it twice, which is, well, twice as nice. The version by Pukka Orchestra, a band from my hometown of Toronto, was a radio staple in 1984, a period when I would have been listening to the radio every evening while doing my grade eight and nine homework. It was a crossover hit, getting attention on the alternative, rock, and pop stations and aided by being a popular track to meet Canadian content regulations; though with the song being written by an American, it only counted as 50% CanCon.

I touched on Tom Robinson’s beginnings when The Tom Robinson Band was part of modern rock’s breakthrough year of 1977, as well as his role as a champion of gay liberation. He then had a minor hit in 1979, “Sartorial Eloquence (Don’t Ya Wanna Play this Game No More?),” co-written with Elton John, before forming the band, Sector 27. The band, despite some early positive responses, failed to take flight due to a breakdown of their management company, leaving Tom broke and despondent. This prompted him to move to a friend’s place in Hamburg, Germany and then to East Berlin. During then he wrote his first solo record, North by Northwest, which was released in 1982. He also released a non-album single in 1983, “War Baby,” that reached #6 in the UK chart and #1 in the indie chart, reviving his career.

The second track on the A-side of North by Northwest was a song called, “Atmospherics,” which was one of two songs on the LP co-written with Peter Gabriel. It had an easygoing feel with a funky, thick bassline and beat. Robinson’s echoey, dark-edged, offhand delivery of the lyrics was offset by the chorus that had a lighter feel. The song had an electronically flavoured, atmospheric break around the two-thirds mark, of which the lyric that followed was, appropriately, “Atmospherics after dark / Noise and voices from the past / Across the dial from Moscow to Cologne,” and thus the title of the song. This is the version heard on the Spotify playlist. Also in 1982 Robinson issued a 12” EP, Atmospherics, that featured a newer, slightly longer version of the song along with four other tunes. It had a less atmospheric feel, was quicker, and was smoothed out into more of a pop vein with added keyboards and horns and a less ominous break. In 1983, the song appeared again as a 7” single, this time titled, “Listen to the Radio (Atmospherics),” though the track listing styled it as, “Listen to the Radio: Atmospherics.” This title referenced the song’s most prominent, repeated lyric. Then again in ’84 it appeared again as a 12” with an extended version. The two latter versions appeared on a 1984 compilation, Hope and Glory, and is the version heard on the YouTube playlist. In 1983, “Listen to the Radio: Atmospherics,” reached #39 in the US singles chart.

As noted by Robinson himself in the comments of the YouTube video, the song was written in Hamburg in ’82 near the referenced Onkel Pö club. The lyric about taking a tram was an artistic liberty since Hamburg didn’t yet have those, but he would have seen them during his time in East Berlin. The lyric, “Find a bar, avoid a fight / Show your papers, be polite” was also undoubtedly a nod to life in the restrictive environment of East Berlin at the time. By the time the recording of the music was being completed, it didn’t yet have a vocal. Tom dashed off the lyrics quickly in an office in the studio and, he noted, if he’d known just how common the ‘listen to the radio’ reference was in music, he would have been inclined not to use it. The quick, offhand nature in which the lyrics were written informed the song’s casual telling of a life in the city.

In early 1980s Toronto, there was a vibrant live music scene clustered along Queen St. West where a variety of bands were expanding the sounds coming out of city. Among them was the trio of Graeme Williamson, Tony Duggan-Smith, and Neil Chapman, who played the bars with a rotating cast of players working among the various acts in the scene. The band name originated from when Tony’s British grandfather, who had spent time in India, wrote him a letter in which he was dismissive of Tony’s musical endeavours. His elder suggested that Tony join a ‘pukka orchestra,’ which drew on a Hindi word suggesting something more genuine or of high quality. The trio immediately knew they had their name.

The Pukka Orchestra in a promo photo from their soon to be defunct record label, Solid Gold Records

By 1984, Pukka Orchestra were finishing their debut, self-titled album. Their label, Solid Gold Records, was dissatisfied with the LP’s lack of a bona fide single. The label brought the band the Tom Robinson song, which they were reluctant to consider since they only wanted their own music on the LP. However, with the Peter Gabriel writing credit, Neil Chapman was smitten and willing to give it a try, and through the recording of the song the band came to like it. It fit into their Queen West, humour-infused pop style. They drew off Robinson’s latter, ‘83/’84 versions of the song, delivering a polished, lighter, but completely straight-up rendition of the song. Williamson’s voice even sounded a lot like Robinson’s. They shortened the title to just, “Listen to the Radio,” and watched the song reach the top twenty in Canada.

Unfortunately, Pukka Orchestra was not able to capitalize on that success and the popularity and controversy of the follow-up single, “Cherry Beach Express,” which sang about police brutality within the gay community in Toronto. Solid Gold Records folded, shutting down their receipt of royalties and the distribution of their music, and thus cut short the upward trajectory of their success. Soon after, Williamson, while visiting his homeland of Scotland, developed problems with his kidneys and spent months in a Glasgow hospital on a dialysis machine. The band raised money to help him out and he recovered after a transplant. The band got around to recording a second LP in the late ‘80s, but Williamson decided to return to Scotland and pursue a writing career, leaving Pukka Orchestra defunct. Some of the recordings would appear in a 1987 EP and then in a new, 7” single in 1992, but without the band together to promote it, success didn’t come. Their album was also out of print, but after a CD release in 2000 made it available again they have sustained as a cherished, great band of the 1980s, having left us with a great LP and the timeless fun of their cover of “Listen to the Radio.”

“Physical (You’re So)” \ Adam & the Ants (1980) & Nine Inch Nails (1992)

Following the 1979 release of the excellent debut LP, Dirk Wears White Sox, Adam Ant (Stuart Goddard) re-organized the personnel, sound, and look of his band – and not by choice given Malcolm McLaren stole his band to form Bow Wow Wow. Dressing up in a look that mixed American aboriginal war make-up with an old British naval jacket and pirate scarves, the new version of the band adopted the Burundi beats of Africa and arrived in the late summer of 1980 with a sound that would conquer the UK charts for the next year.

The “Dog Eat Dog” single with “Physical (You’re So)” on the back cover

Before their next album, Kings of the Wild Frontier, arrived in November 1980, two singles were released. The first was the album’s title track, issued in July, which didn’t catch fire but did give them their first charting single. In October came “Dog Eat Dog,” which would reach #4 in the UK singles chart, setting up the success of the ensuing album and the third single, “Antmusic.” The album would go to #1 in the UK.

The B-side to “Dog Eat Dog” was a track called, “Physical (You’re So).” It was a reworking of a song they’d been playing live since 1978, “Antpeople,” that had morphed into “Physical” or “You’re so Physical.” Versions of the song were recorded first for a John Peel session and then as a demo when recording the first LP. The version that appeared on the “Dog Eat Dog” single was recorded during the Kings of the Wild Frontier sessions but wouldn’t end up on the album (though it was included in the North American release and later, expanded CD releases). This version was slower, a rough dirge that allowed Ant to lean into the sexual themes of the song, a not uncommon topic for him. The one sign that the song pre-dated their new, beats-driven sound was the very lack of tribal beats, though now with two drummers in the band the beats still had a deep forcefulness that underpinned the rough, rock-edged guitar from Marco Pirroni and Ant’s sneering vocal.

Trent Reznor, known by his band moniker of Nine Inch Nails, had arrived on the scene in 1989 with the exciting, invigorating power and menace of the debut LP, Pretty Hate Machine, and album that helped bring industrial music to a broader audience. It would take five years due to battles with his record label before he could follow it up with his second album, the impressive The Downward Spiral. In the intervening years NIN only offered fans a couple of EPs, both issued in 1992, Broken and its remix companion, Fixed.

It was the early days of compact discs and bands were having fun with the concept of the hidden track. On vinyl, a hidden track would just be an extra song that wasn’t included on the label, but with the expansive capacity and digital tricks of CDs, a song could not just be hidden on the label but could be buried on the disc by putting it many minutes after the final song. Though Broken’s initial release had two extra tracks on a separate disc, the subsequent mass release placed them, unlabelled, in the 98th and 99th slots of a single disc (most players couldn’t display a three-digit track number, so that would have been the max number of track slots). This meant you had to fast forward to these hidden tracks or allow the disc to play through 92 blank, one-second tracks to reach them. This was tedious and annoying, and I never understood why artists resorted to hidden tracks.

Trent Reznor in the early days, before he cut his hair and beefed up

The payoff of getting to these tracks was the joy of hearing the 98th track, the cover of “Physical (You’re So).” The 99th was a track, “Suck,” by the band, Pigface, of which Reznor had been a member and thus a co-writer, though his version on Broken was completely reworked into a new version.

I knew of the Broken EP before I bought it, as “Wish,” “Happiness in Slavery,” and “Physical” were all regular plays at The Dance Cave, the nightclub I attended practically every Friday and Saturday night from 1991 through 1994. I didn’t discover that “Physical” was a cover until my girlfriend at the time (and later my first wife) put it together, having been a big Adam Ant fan and an owner of a vinyl copy of Kings of the Wild Frontier (recall, the song was included on our version). I didn’t even know what the song was called at that point, though the repeated lyric, “you’re so physical,” led to a pretty reliable guess. In those pre-internet days it was exciting to piece together the mystery of the song. I can’t recall what the album’s credits and notes said about it, though I don’t recall finding any reference to Ant on it or the song’s name.

NIN’s version of “Physical” thus arrived after the 92-track break on the disc, breaking the silence with a fantastic opening of a menacing, foreboding bit of guitar feedback (much like the original) and static leading to a crack of electronic drums before falling into the steady dirge of the Adam Ant composition. It was a straight-up cover, but with NIN’s industrial rock feel it also gave it a bit of a genre change. Ant’s original pre-dated the full arrival of industrial music but could be argued was a decent fit to the genre. Reznor kicked up the power and dark threat of the song, using the electronics and modern technology to kick the song into higher levels of an angry chorus and building from a sparse sound into a melange of chaotic, encompassing electronics and caustic guitar over the final minutes, before petering out into the same, factory-like atmospherics that had opened the song. It was a great song, staying true to Ant’s original while making it fully a NIN listening experience.

That concludes this batch of originals and covers. With more straight-up covers this time around, it was a more traditional list of cover songs, though still managed to dip into several different genres of rock. I never tire of placing the differing versions together and running through them and will continue to look for more great examples of covers to explore in future volumes.