Cover Songs: Volume 4

Click on streaming service of your choice to listen to the playlist as you read along.

This is the fourth installment of an ongoing series exploring the art of the cover song. In the first volume I outlined the various types of cover songs (Straight-up; Modernization; Tempo Change; Genre Change; Reinvention) which provides the framework for my dissection of cover songs. It will help to read the introduction of that first volume before continuing here.

The Playlist

Heaven \ Talking Heads (1979) & Simply Red (1985)

Lay Lady Lay \ Bob Dylan (1969) & Ministry (1996)

Sorry for Laughing \ Josef K (1981) & Propaganda (1985)

Don’t Tell Me \ Madonna (2000) & Stop \ Joe Henry (2001)

China Girl \ Iggy Pop (1977) & David Bowie (1983)

Because the Night \ Patti Smith (1978) & Bruce Springsteen (1986/2010)

They Don’t Know \ Kirsty MacColl (1979) & Tracey Ullman (1983)

Kitty \ Racey (1979) & Mickey \ Toni Basil (1981)

Stop Your Sobbing \ The Kinks (1964) & Pretenders (1979)

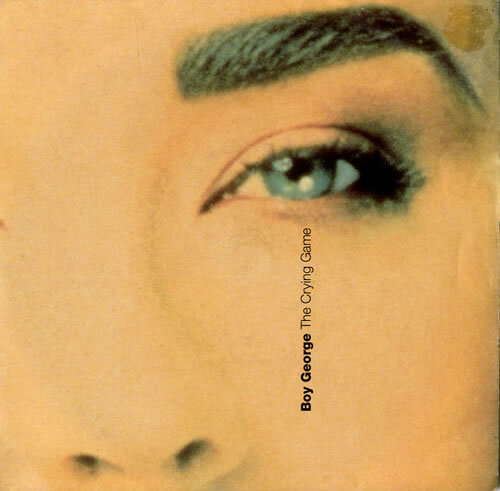

The Crying Game \ Dave Berry (1964) & Chris Spedding (1980) & Boy George (1992)

The Temple \ Original Studio Cast of Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) & The Afghan Whigs (1992)

In this volume we’ll look at more changes of genre, cases in which a song writer covered his own song after it had been recorded by someone else, the reworkings of songs including lyrics, and a cover of a Broadway musical. One of the fun parts of these playlists is getting to hear a wider variety of music styles than normally found at Ceremony, so enjoy.

Heaven \ Talking Heads (1979) & Simply Red (1985)

Talking heads released their third LP in 1979, Fear of Music, which continued their gradual march out of the relative obscurity of CBGBs and New York’s punk scene into broader popularity. It was the second of three consecutive LPs of theirs to be produced by Brian Eno. The album was also the first to introduce their use of rhythms inspired from world music. Propelled by the single, “Life During Wartime,” which didn’t chart highly but provided another in a growing list of classic songs from the band, Talking Heads continued their creative evolution away from their smart-punk beginnings into a rhythm-based mix of pop, new wave, and post-punk music.

One example of that trend was the song, “Heaven,” sitting in the second slot of side two. Not a remarkable song for Talking Heads, the tune was written by David Byrne and Jerry Harrison and was slightly down tempo with a faraway feel, as if being sung from the other end of a large room. It was more melodic than most of the band’s work and fit with their increasing new wave and pop proclivities.

Simply Red’s cover was interesting in that it took the song, seemingly, backwards in time. In 1985, as the R&B and new wave trends of the prior years were ebbing away, the Manchester, England band led by singer Mick Hucknall had a breakout success with their debut LP, Picture Book. The album’s soul and blues feel brought the older vibes of rock’s history up to date, and across five singles was widely embraced by fans, with two songs hitting the top twenty in the UK and scoring a #1 hit in the US with, “Holding Back the Years.”

Simply Red’s version of “Heaven” was not a single, but probably could have been, and was one of the album’s several slower, bluesy songs that offset the soulful energy of the likes of “Come to My Aid” and “Money’s Too Tight (to Mention).” Slowing the song down and leaning into its melody, Hucknell provided a sorrowful tone over piano and guitar accents and a rich, bluesy, bass rhythm. It offered a nice sax interlude too. It was a genre and slight tempo change cover of the original and provided a lovely and compellingly different take. The changes were subtle but offered two very different versions of the song, revealing the strength and versatility of its melody. We were used to British artists covering American soul and blues artists – and even Talking Heads had done so with their cover of “Take Me to the River” in 1978 – but this was a novel take by taking a new wave tune and turning it into a blues track.

Lay Lady Lay \ Bob Dylan (1969) & Ministry (1996)

The album cover for Nashville Skyline

It’s hard to make any list of cover songs without including Bob Dylan, who has been covered by so many over the years. “Lay Lady Lay” is a track that, in particular, has appealed to cover artists multiple times over the years. Dylan’s original appeared on his 1969 LP, Nashville Skyline.” It was his ninth release and the fifth consecutive to reach the top ten in the US. In the UK, it went to #1, the fourth of his albums to do so, and “Lay Lady Lay” cracked the top ten in both countries as the LP’s most distinguished track. The song became a classic thanks to its laid-back feel, simple structure, beautiful melodies, and sublime transitions between the understated verses and the heightened chorus. The song’s simplicity provided an easy palette for others to work off.

The album cover for Filth Pig

One of the more startling and intriguing covers came from Ministry, the industrial-rock band led by Al Jourgenson. Featured on the 1996 LP, Filth Pig, the band had originally performed it with Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder on vocals for a benefit concert in 1994. Their version stayed true to the original’s feel and structure, but presented fully via the caustic, dark moodiness of Ministry’s industrial-metal sound. Of course, a severe genre change always makes for an instantly curious cover and moving from a folk-country original to a heavy rock cover couldn’t be a more consummate example. What I liked about this cover was the use of bass to carry the melody, the explosiveness of the chorus to fully realize the energy only subtly provided in the original, and move of the vocals not entirely to the back, but to a much less prominent point compared to Dylan’s. At a run-length two and a half minutes longer, Ministry took the time to luxuriate in the melodies and power of the composition. It wasn’t a song I would have thought would make an easy transition to industrial rock, but Ministry pulled it off amazingly well. As we often note in these volumes, a good song is a good song, regardless the genre.

Sorry for Laughing \ Josef K (1981) & Propaganda (1985)

I’ve known Propaganda’s version of this song since I bought the album, A Secret Wish, in 1985, drawn to it by the fantastic new wave synth tune, “p:Machinery.” “Sorry for Laughing” was the track that followed that song on the album and I always liked it. It was a starker blend of industrial beats and pop melody from singers Susanne Freytag and Claudia Brücken, building into a catchy tune as the icy synths blended in over the later stages of the song. It was a track I often added to my mixtapes for my Walkman during my daily commutes to high school.

The 7” cover for the Josef K single

Josef K was a band that escaped my notice until recent years. When French act, Nouvelle Vague, known for its bossa nova covers of ‘80s new wave songs, covered “Sorry for Laughing,” I assumed it was a cover of Propaganda’s version. When I saw on the credits that it was originally by Josef K, I wondered, ‘who is that?’ Well, it wasn’t a person but a Scottish band, part of the roster of post-punk acts on Postcard Records along with Orange Juice and Aztec Camera. Josef K released several catchy tunes over their brief tenure from 1979 to 1982, with just one LP, June 1981’s The Only Fun in Town (there was also an unreleased album with some overlapping songs, Sorry for Laughing, that was available in bootlegs before getting a vinyl release in 2012). The album was recorded in Brussels and “Sorry for Laughing” was the album’s closing track. It was also released as a single that prior February, but unlike most of their other singles had failed to place in the UK’s indie chart. Featuring their stark sound and built on strumming guitars, a catchy beat, and the almost Iggy Pop-like vocal by Paul Haig, the track was typical of their stripped down, dark wave sound.

Propaganda was a German band and A Secret Wish was their debut LP. Championed in the UK by the likes of DJ John Peel and journalist Paul Morley, they signed to Trevor Horn’s ZZT Records and enjoyed early success with the singles, “Dr. Mabuse” (1984) and “Duel” (1985), both of which would appear on the LP in 1985 which cracked the top twenty in the UK. Their electronic take on the Josef K song was a genre cover, with the change in instrumentation making for a very different version. Much fuller and broad sounding and with a greater pop element, their version still held true to the mix of rhythm and melody of the original and its catchy chorus.

Don’t Tell Me \ Madonna (2000) & Stop \ Joe Henry (2001)

The next few tracks will focus on covers by the song’s original writer but in which the song had been recorded by another artist. So I suppose that doesn’t make it a true cover version, but when the song already existed in the greater consciousness and was even popular but under the association of a different artist, it was hard not to see the writer’s version as a cover. Whether this was the writer looking to lay claim to it, offering their own version to show how they would have done it, or simply in celebration of a song of theirs they liked, this not uncommon situation has led to some interesting variations on tunes over the years – these are but a few.

Pop stars like Madonna often don’t write much of their own material. Sometimes it’s their label looking to ensure a ‘can’t miss’ talent delivers by ensuring quality songs to sing; or once established, their fame grants them the opportunity to avail themselves to a ready list of songwriters and great songs with which to work. In the ‘50s and ‘60s it was normal practice for song writers and performing artists to be separate, with no expectation of the performer writing their own material. By the ‘70s, especially in the rock world, this had changed, and most artists wrote their own material. Pop music has always sustained the division of labour. In contemporary times, we have seen a return to the ‘50s model in which teams of writers crank out tunes using formulas, data, and testing to ensure a performing talent’s releases maximize their potential for success.

Madonna has straddled the line, writing many of her own songs including several of the early hits that made her a huge star. However, she has had a lot of help over the years, whether it was taking her initial melodies or lyrics and flushing out the music with others, to taking others’ songs and tweaking the lyrics and music to her own desires. On her 2000 LP, Music, such was the case with most of the songs, credited to Madonna and a list of co-writers, chiefly French-Swiss producer, Mirwais Ahmadzaï as well as co-producer, William Obit. Her work with them resulted in a more electronic feel to her music, blended with the country music flavouring she with which she was experimenting.

Joe Henry

Joe Henry was married to Madonna’s sister, Melanie Ciccone. Based in New York, he had been releasing albums since his debut, Talk of Heaven, in 1986. His style was a mix of blues, jazz, folk, and country. In the late ‘90s he (or perhaps it was Melanie) passed along a demo of his song, “Stop,” to Madonna and she decided to use it on her album. Working with Ahmadzaï, Madonna converted the song from Henry’s tango-like, acoustic-rock tune into a country-electronica track consistent with the rest of her album. She also changed the title, using the first part of the lyric, “don’t tell me,” as the title instead. Her version was the second single from the LP, and it went top ten in the US, UK, and many other countries around the world. While promoting it, she showed off her burgeoning guitar skills with an acoustic performance on The Late Show with David Letterman, which in some respects offered a version closer to the original.

“Stop” was released by Henry on his LP, Scar, in May 2001, just eight months after Madonna’s LP was issued. Henry has amusingly commented that his version was written as a tango, while hers was written as a hit. Carried at a laconic tempo, the song was a wonderfully sultry mix of strings, percussion, and light, twanging guitar. This is a great example of how a good song with good bones can sound good in any format. Give Madonna and Ahmadzaï credit for reinventing it for their genre, and Henry for writing such a sturdy song from which to work.

China Girl \ Iggy Pop (1977) & David Bowie (1983)

Iggy Pop and David Bowie in Berlin

This was another example of an artist covering his own song after having given it to another artist. The relationship between David Bowie and Iggy Pop both personally and artistically was lengthy and productive. The two first came together when Bowie encouraged The Stooges to re-unite for a third LP, 1973’s classic proto-punk release, Raw Power, which Bowie produced. In 1976 Bowie moved from California to Berlin to both immerse himself in the emerging Krautrock scene, with their experimental mix of rock and electronics, and to get away from the sex and drugs lifestyle that was hobbling his well-being. Iggy, also in need of a healthier change in scenery, joined him.

While Bowie started work on his ‘Berlin Trilogy’ with producer Brian Eno, he also co-wrote and produced an album with Pop, The Idiot. The album was Pop’s first solo release and the first work to be issued by either artist from their Berlin based efforts. It was released in March 1977 and re-launched Iggy’s career, due in no small part to both Bowie’s and his band’s help. While “Nightclubbing” was the standout track on the album, the singles would be “Sister Midnight” and then, “China Girl.” Like most of the tracks on the album, “China Girl” was co-written by Pop (lyrics) and Bowie (music) and musically was consistent with The Idiot’s raw, rock feel. Bowie was coming off his plastic soul/Thin White Duke period which featured soulful, sax-filled, broad compositions. Writing more direct songs with Pop helped him shift to a new direction, though in “China Girl” some of the expansive elements, background synths (the inspiration for their Berlin work), and sax accents could still be heard. Iggy’s deep voice and emphatic phrasing still made it more of a rocker, consistent with Iggy’s style.

By 1983 Bowie had gone through his Berlin trilogy and was riding high on his most recent LP, 1980’s Scary Monsters…..and Super Creeps, his most commercially successful release since 1972’s Ziggy Stardust, and the immense popularity of his 1981 collaboration with Queen, the single “Under Pressure.” He was then working on a more accessible, pop-styled album, Let’s Dance, with Chic’s Nile Rodgers as co-producer. The album melded a smoother, R&B groove into Bowie’s distinctive song writing and sound. They took “China Girl” and updated it, adding an Asian guitar riff overtop to match the song’s feel to its title. The song also had a bluesy guitar solo in the middle courtesy of Stevie Ray Vaughan, who played on the entire album. Bowie, similar to Pop, had a deep voice, but as a significantly more adept vocalist brought more nuance to the song and didn’t repeat the snarling styles Iggy had employed. Each put their own personalities on the song, as it should be.

Iggy’s version of “China Girl” didn’t chart, while Bowie’s, as the second single from Let’s Dance, continued his success by going top ten in both the US and UK. Let’s Dance would be Bowie’s best-selling LP of his career.

Because the Night \ Patti Smith (1978) & Bruce Springsteen (1986/2010)

In 1977 Patti Smith and Bruce Springsteen were very different artists at different points in their career. Smith was a highly regarded punk and rock performer coming out of the New York’s CBGB underground scene. Known for her poetry and as a rare female rocker, she hadn’t yet found a broader fanbase for her acclaimed first two albums. Recuperating from a bad accident after falling off a stage in 1976, she was also in the process of recording her third LP, Easter, with neophyte producer, Jimmy Iovine.

Iovine had been, to that point, an engineer working at the Record Plant studio in New York. After working on Springsteen’s 1975 epic LP, Born to Run, he was also working on The Boss’ follow-up, Darkness on the Edge of Town, which was being recorded that summer simultaneous to Smith’s LP and in the studio next door, no less. While listening to Springsteen burnish is ascending stature as a leading figure in the rock world, he was also dealing with Smith trying to find a way to shape her unique rock-poetry into an accessible form. Patti was also not a proficient song writer, taking a long time to put her songs together. Iovine needed tracks to complete the album and he strongly felt it needed a hit to bring Patti the exposure she so richly deserved. He shared this sentiment with Springsteen.

“Because the Night” was a song Bruce had been working on for his new album. A demo had been recorded with unfinished lyrics and he was struggling to finish it. It was becoming clear it wasn’t destined for inclusion on the album. When Iovine told him about Patti, a fellow New Jerseyan, and her need for songs, Bruce offered “Because the Night,” passing him a cassette with the demo recording. Smith resisted taking the song, since as a poet she wanted to write her own. She finally gave it a listen one night in her New York apartment while waiting for a phone call from her boyfriend, Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, who lived in his native Detroit. As the night wore on and Fred hadn’t called, Patti listened to the song over and over, drawn to it, knowing it was a hit, but regretting the idea that her potential first hit would be with someone else’s song. If there was a saving grace, it was the lack of lyrics. Bruce had provided a chorus but hadn’t figured out the verses. By the time Fred called Patti past midnight, she had written verses to the song inspired by her relationship and her yearning for Fred’s call. The song was becoming hers.

Patti had a great band that included guitarist Lenny Kaye, a studied musician and rock historian. With him and Iovine’s contributions, they recorded their version of “Because the Night.” While Bruce’s version was, as Patti described it, “almost Latin in its movement,” her band put their punk-rock energy into it. Using Bruce’s typically subtle, tinkling piano intro, Patti provided the quiet opening lyrics before the drums exploded the song into the broader expanse of a quintessential Springsteen song. In his typical fashion, it then really opened up for the epic chorus. Ironically, Bruce was working on an album that was trying to move away from those sweeping, epic moments, as Darkness on the Edge of Town would see Springsteen abandon the large scale ballads of his prior albums in place of tighter, more direct rock tunes built around traditional verse-chorus structures. Patti, with her fantastic voice, was perfect for the song. Smith’s lyrics reflected her mood of longing as she waited for her lover’s call. “Have I doubt when I’m alone / Love is a ring, the telephone / Love is an angel disguised as lust / Here in our bed until the morning comes.” Her echoing, plaintive voice mixed vulnerability with defiance, knowing she and Fred would conquer their nights apart through their shared love and the thoughts of being reunited.

Easter was released in March 1978 and “Because the Night” was issued at the same time as the album’s first single. It reached #13 in the US singles chart and cracked the top ten in the UK. It was her seventh single and the first to reach the charts at all, much less ascend to their upper ranks. The song also propelled the album into her first top forty placing in the US and UK.

Bruce often played live the songs he’d written and given to others. “Fire” for the Pointer Sisters was a highlight of his shows, as would be “Rendezvous,” a 1982 song for Gary U.S. Bonds. Therefore, it was not a surprise when Bruce started performing “Because the Night” on his tour for the Darkness album. He adjusted her lyrics, working through different live versions as he made it his own. Patti’s lyric, “Take my hand come undercover / They can’t hurt you now,” became variations of, “Take me now as the sun descends / They can’t hurt you now / They can’t hurt us now.” And Patti’s verse, quoted above, became for Bruce, “What I got I have earned / What I’m not baby I have learned / Desire and hunger is the fire I breathe / Stay with me now till the morning comes.”

“Because the Night” has been a standard on Bruce’s tours ever since. The first recording of his available for purchase was a live version on this 1986 box set, Live/1975-85. A studio version was made available on this 2010 album, The Promise, taking recordings from his Darkness sessions and adding modern vocals and musical touch-ups. His live versions are epic, huge, booming and energetic versions that filled the stadiums in which he performed, while the album version was more understated and slowed down. Interestingly, he used Patti’s lyrics in the studio version. His versions also have, by necessity one would think, Clarence Clemons’ sax to help bolster the song’s interludes. While Patti had a rawer, punkier energy, Bruce’s had his usual, big band depth and fullness.

A cover song? Two different versions? Co-written? Regardless, it was a great song brought to life by two amazing artists.

They Don’t Know \ Kirsty MacColl (1979) & Tracey Ullman (1983)

This track is a slight variation on the dynamic we covered in the past few songs. “They Don’t Know” was a song first written and recorded by Kirsty MacColl, but who then helped Tracey Ullman with her own version. So in this case it was an artist indirectly covering her own song. This is also the first of a couple of songs that looks into why a straight-up cover resulted in a hit for the cover artist but not for the original. This is a common theme in our volumes of cover songs since it’s such an interesting dynamic.

Kirsty MacColl was an unknown singer, or perhaps only known as the daughter of 1940s and ‘50s actor, singer, and activist Ewan MacColl. In 1978 she was performing under the name Mandy Doubt for a band, Drug Addix, who released an EP on Chiswick Records and had done some demos for indie label, Stiff Records. While the band didn’t make an impression, she did, and was able to sign with Stiff to release a single as a solo artist. The result was 1979’s “They Don’t Know.” MacColl’s love of the Beach Boys resulted in her use of ‘60s melodies and harmonies, resulting in an extremely catchy, retro-styled pop single. MacColl was a fantastic singer who would go on to a modest career both solo and as a guest singer for many other artists, especially those produced by her husband as of 1984, Steve Lillywhite. However, “They Don’t Know” didn’t give her much of a start since, despite being popular on the radio, Stiff didn’t issue enough singles for purchase and the sales didn’t get her onto the charts. It’s rumoured conflicts between Kirsty and Stiff Records’ president resulted in the lack of promotion for her songs.

Trace ‘Tracey’ Ullman was a British theatre actress, singer and dancer, having starred in several London West End musicals. Switching to comedy and television in 1981, she starred in a sketch comedy show, Three of a Kind, with Lenny Henry and David Copperfield (no, not the illusionist). After a chance encounter with the wife of Stiff Records’ president, she had an opposite experience to Kirsty by having her musical career launched. She was invited to record an album, which resulted in 1983’s You Broke My Heart in 17 Places, a collection of covers of various pop songs both from the ‘60s, such as the first single, “Breakaway,” which reached #4 in the UK singles chart, and more recent late ‘70s songs, such as Blondie’s, “(I’m Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear.” A common bond between all the songs both old and recent was a strong, melodic-harmonic pop sensibility, which clearly fit with Tracey’s voice and performance style. The album reached #14 in the UK album chart, due to both the albums’ catchy sound and Ullman’s theatre and television celebrity.

On the album, Ullman covered two songs by Kirsty MacColl. After “Breakaway” became a hit and prior to the album being recorded, Pete Waterman, who had written hits for Stiff on behalf of the Belle Stars, suggested to Kirsty that “They Don’t Know” be recorded by Tracey. MacColl not only granted this but came in to the studio to provide backing vocals, including the high-pitched, “baby,” lyric which was beyond Ullman’s vocal range. Tracey also recorded another song written by Kirsty which became the title track to the album.

Ullman’s version of “They Don’t Know” was a straight-up cover; so much so that it was suspected the music from the original was used as a backing track, though that was not the case. Ullman’s voice was thinner and lacked the character of MacColl’s and was therefore a weaker version. Nonetheless, the popularity of the actress helped her version became another hit. Released in September 1983, it reached #2 in the UK singles chart. And though Tracey was not well-known in the US, the song’s video propelled it to broad exposure on MTV thanks to the station’s president being a fan. The song reached #8 placing in the US singles chart. The video’s notoriety was certainly helped by a brief appearance by Paul McCartney. Tracey had recently filmed a cameo for the former Beatle’s upcoming film, Give My Regards to Broad Street, so he returned the favour. The success of the video stateside, as well as her 1983 marriage to American producer, Allan McKeown, helped Ullman launch a sketch comedy show in the US, The Tracey Ullman Show, on the new Fox network in 1987. The show was a success and notably provided the launch pad to the animated show, The Simpsons. Ullman is now a household name in comedy, due in no small part to the song from Kirsty MacColl; she has never gone back to resume a musical career, leaving her hit singles and one album as her musical legacy.

Kitty \ Racey (1979) & Mickey \ Toni Basil (1981)

Moving on from the situation of an artist covering their own song, we have a case somewhat similar to “Stop,” wherein an artist covered a song and re-worked the lyrics to make it something different. This is also like “They Don’t Know,” being another example of a straight-up cover becoming a huge hit when the original was not.

Racey was a British band that had a few hits over the late ‘70s. They were part of the fading glam scene in England, working with famed producer and label owner, Mickie Most, and the legendary song writing team of Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman. Racey only recorded one LP, 1979’s Smash and Grab, a glam rock album that was best forgotten, though held their many improbable hits (two top tens in the UK as well as another in the top forty). On that album was the song, “Kitty,” which was not one of the singles. Mixing a catchy drum and bass rhythm with an organ and a chorus straight out of the ‘50s, the song had an undeniable quality to it.

Toni Basil (Antonia Basilotta) was an American singer, actress, dancer and choreographer who had worked with the likes of David Bowie and Talking Heads to choreograph and/or direct their tours and videos. She’d also done some singing for film and television since the 1960s, and in 1980 went into the studio and, at the age of 37 and much the same as Ullman would do a couple years later, recorded an album of cover songs that included Racey’s, “Kitty.” To account for the change from a male singer to female, she reversed the original lyrics to a woman singing towards a man, and thus the change from “Kitty” to “Mickey.” She also added a chant to start the song, “Oh Mickey you’re so fine / You’re so fine you blow my mind / Hey Mickey / Hey Mickey.” The song benefitted from an update from its glam origins to a sharper, new wavish composition. Still using organ, the music was tighter, more forceful, and Basil’s vocals added more personality. The catchiness of the song, with its retro-rock ‘n’ roll feel, came through much stronger than the original. Otherwise, it was a straight-up cover.

“Mickey” was first released in the UK in 1981 to little attention. A re-release in ’82 fared better, reaching #2 in the UK singles chart. It then saw #1 success in Australia and the US over the course of 1982, becoming one of the biggest songs of the year and the decade. Its success was undoubtedly helped by the video of Basil dancing against a white background in a cheerleader’s outfit, taking advantage of her choreography and dance skills along with other similarly dressed dancers. It was a very popular video on the new MTV channel, launched in August 1981 which was between “Mickey’s” two release dates. Why did Basil have a hit when Racey’s was ignored? Given the song’s dynamic and the help of the MTV era, a female-presented version of the song carried it better. In 1979 glam was dying away, and though Racey had hits, “Kitty” didn’t sit as well with their rock sound that was driving their success. When Basil switched it to a cheerleading chant, combined with a dance routine, the combination was the right formula for early ‘80s pop – an easy singalong track that was friendly for radio and television.

For Racey, it was probably a frustrating situation since they didn’t write “Kitty” and it wasn’t released as a single, so they would have made no money off the song aside from its contribution to their album sales. Chinn and Chapman, as they had so many times before, had themselves another huge thanks to Basil’s update and popular video.

Stop Your Sobbing \ The Kinks (1964) & Pretenders (1979)

Chrissie Hynde, an American who ended up in the London punk scene of the late ‘70s and was putting a band together, chose a cover of an album track from legendary mod-rockers, The Kinks, for an early demo. Covers have long been a good way for new bands to both find their legs and to get attention. As an Ohio native, Hynde had long been a fan of early garage rock and no doubt appreciated the early work of bands like The Kinks.

“Stop Your Sobbing” was written by Ray Davies and was the second last track on The Kinks’ debut LP in 1964. The album was part of the burgeoning trend of mid-‘60s, raw sounding, garage rock acts (as documented in the Builders of Modern Rock playlist). The self-titled album was notable for the garage rocker, “You Really Got Me,” which as a #1 UK hit and top ten US single that helped forge the way for The Kinks’ ascendency to classic rock royalty. “Stop Your Sobbing,” however, was a simpler, harmony-based track that harkened back to the simple structures of late ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll and early Beatles records.

Hynde and her new band, Pretenders, got Nick Lowe to produce their version of “Stop Your Sobbing,” which was released as their first single in January 1979. It would also be included on the band’s debut LP, released a year later. Their version sped up the song, brought on all the force of their power pop sound, and offered the wonderfully charismatic vocals of Hynde. More melodic and evenly paced, it was a pop masterpiece and gave Pretenders their first hit with a top forty placing in the UK. It was therefore mostly a combination of a tempo change and modernization cover, revealing the strength of the original and giving it power not immediately apparent in Davies’ delivery.

Hynde and Davies would meet thanks to this cover and go on to have a relationship and a child together. Pretenders would again cover The Kinks in 1981 with their single, “I Go to Sleep,” which was covered in volume 1 of this series of cover songs.

The Crying Game \ Dave Berry (1964) & Chris Spedding (1980) & Boy George (1992)

Like most people of my generation, I came to awareness of this song thanks to the 1992 film of the same name and the song recorded for its soundtrack by Boy George, who at that point was working on his uneven, post-Culture Club solo career. He’d released four solo albums (one credited as the band, Jesus Loves You) to mixed results and, after having a #1 hit in ’87 with “Everything I Own,” had struggled to push any of his singles to high charting results.

“The Crying Game” was a song written by Geoff Stephens, a British song writer who’d penned many hits in the ‘60s for the likes of his own act, The New Vaudeville Band, as well as Manfred Mann, Cliff Richard, Tom Jones, and others. Dave Berry was a teen idol performer in Britain, known for always performing with his face partially obscured. As was common for the time, and especially for teen idols, he sang songs written by others and had several top forty hits in the UK between 1963 and 1966. He was the first to record “The Crying Game,” taking it to #5 in the UK singles chart in 1964. The recording featured guitarists Big Jim Sullivan, a legendary session player who performed on 54 UK #1 hits, and a pre-Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin, Jimmy Page. The song had a typically ‘60s echoey and saccharine pop style but was given some personality thanks to the guitar work of its talented contributors.

I’ve recently been exploring the work of guitarist Chris Spedding – who has played a part in so much of the music covered on Ceremony – and have been adding his music to my library. Therefore, his songs have been cropping up in my randomized playlists. I was a little startled when his version of “The Crying Game” recently came up, and it was hearing his version that prompted me to include the song on this playlist. He released it as a single in 1980, and his cover was mostly straight-up, keeping the faraway vocal, slow tempo and blues guitar. His version did give it a rock edge, modernizing it to be consistent with the styles of the late ‘70s.

Boy George’s version was an electronic take, leveraging his bluesy vocal with a light, symphonic-synth backing and a nice, melancholy, guitar-like accent that captured the tone of the song. The faraway, dreamy essence of the original was brought to greater fruition through this treatment, scoring the singer a #22 chart peak in the UK singles chart and #15 in the US, making it the last time Boy George would see his name at such lofty chart heights. His cover was a very good modernization and a bit of a genre cover, though was so true to the original in spirit and tone as to also feel like a straight-up approach. Regardless, it re-introduced the song for a new generation in a way that Spedding’s version, good as it was, failed to achieve.

The Temple \ The original cast of Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) & Afghan Whigs (1992)

In 1992 I was spending most of my weekends at a Toronto night club called The Dance Cave. It was a great spot to hang out, dance, and hear a fantastic mix of alternative music both new and old. It was the height of the grunge era and much of the club’s music was filled with the raw guitar of that genre. One night I was with my friend Jorge, whose ears peaked up during one song and as he laboured to identify the song. “Is that… I know that… ah, what is that?” After a minute, he cried out, “Jesus Christ Superstar!”

The DJ at the Dance Cave, Stephen Scott, often played album cuts along with the popular singles and hits of the times. That evening he was playing, “The Temple,” a cover of a song from the Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice musical by Cincinnati band, Afghan Whigs, one of the many great grunge acts from the indie label, Sub Pop.

“The Temple” appeared on Afghan Whigs’ third LP, Congregation, their January 1992 LP that brought them critical acclaim and paved the way for a major label signing and later, mild chart success. They were part of the rise of alternative music that year, driven by Nirvana’s release of Nevermind the prior fall. The Whigs’ frontman, Greg Dulli, was a fan of Jesus Christ Superstar and selected the song to be covered on the album. Of course, the musical, the third project of Webber and Rice, had been a sensation two decades prior. It was issued first as a studio recording in 1970 featuring Deep Purple’s new vocalist, Ian Gillian, before it saw its Broadway debut the year following. The album was an immense success, going to #1 in the US and selling millions of copies.

Jesus Christ Superstar mixed rock music with the usual, dramatic compositions of stage. Hair had been a big success a few years earlier and Superstar adopted a similar approach, mixing the ‘60s rock sounds into the score. Typical of Webber’s approach, the music was designed for broad appeal and accessibility, though in this case the subject matter did come with some controversy. “The Temple” was a scene in which Jesus found the place of worship being used as a marketplace, and he angrily sent the merchants out. He was then implored by a growing group of lepers to heal them. The song therefore shifted through different movements. A guitar-led opening segment with a repeated chorus from the merchants was followed by a keyboard and horns segment leading to the tumult of their expulsion. Jesus (Ian Gillian) then declared the temple reserved for prayer in a classic rock, wailing vocal, which was then immediately followed by an introspective, reflective moment accompanied by strings before the lepers repeated the same chorus as the merchants, but with the lyrics changed for their differing appeals. The merchants had been hawking their wares, while the lepers were seeking relief from their affliction.

Album cover for Afghan Whig’s Congregation

Afghan Whigs’ version was mostly straight-up, since grunge was but an updated, punky variant of classic rock. In typical grunge fashion, the guitars were rawer, and the drums a little looser and crashing around in the background to create a larger sound. The keyboard and horn interlude was omitted and the reflective moment carried by a quieter combination of guitar and drums rather than strings. With Dulli providing all the vocals, the multi-voiced choruses of the original were naturally different. Therefore, most of the song was a grunge-rocker, built around the originals’ opening and closing matching segments.

I include this track as an example of how modern rockers can surprise with their influences and inspirations. I don’t know of too many rock acts that have reached for musicals to source material. Usually those two realms keep a safe distance apart – personally, I generally despise musicals and Jesus Christ Superstar is no exception. I’ve never seen it and even checking out the excerpts from it for this write-up, it isn’t encouraging me further. Grunge, however, was a dynamic of reaching back to the classic rock era and melding it with the punk rawness and energy of the late ‘70s. Afghan Whigs were one of the heavier and rawer contributors of that sound, and their interpretation of “The Temple” stayed true to their sound, reducing the drama of the original in making it their own.

That concludes this selection of originals and covers. In this volume we focused on a slightly tighter timespan and delved into the theme of artists covering their own material originally recorded by someone else, an artist assisting with the cover, more examples of covers becoming much bigger than the original in terms of success, and a different source of drawing from a Broadway musical. Once again hearing the originals and covers side-by-side allows the opportunity to appreciate the differences in approach and styles. I hope you’ve enjoyed this sample and stayed tuned for more volumes of cover songs.